This is the second in a four-part series outlining the Philadelphia 76ers’ plan to build a $1.3 billion basketball arena in Philly’s Center City. Throughout the series of in-depth, deeply reported stories, Boardroom will identify the major players of a proposal that has become a complex web of so many aspects of Philadelphia life that will play a large role in determining the long-term future of Center City and Philly as a whole.

Part I: For David Adelman and the 76ers, Big Arena Dreams Come With Even Bigger Obstacles

Part III: 76ers & Chinatown: Downtown Arena Proposal Forms Deep Divisions

Part IV: The 76ers Want a New Downtown Arena. Here’s How They Get it

The biggest threat to the 76ers getting their new arena could be Comcast Spectacor, their current landlord at Wells Fargo Center.

In every major city in the world, perhaps the most fundamental relationship you’ll find is between landlords and tenants. It’s certainly no different in the City of Brotherly Love.

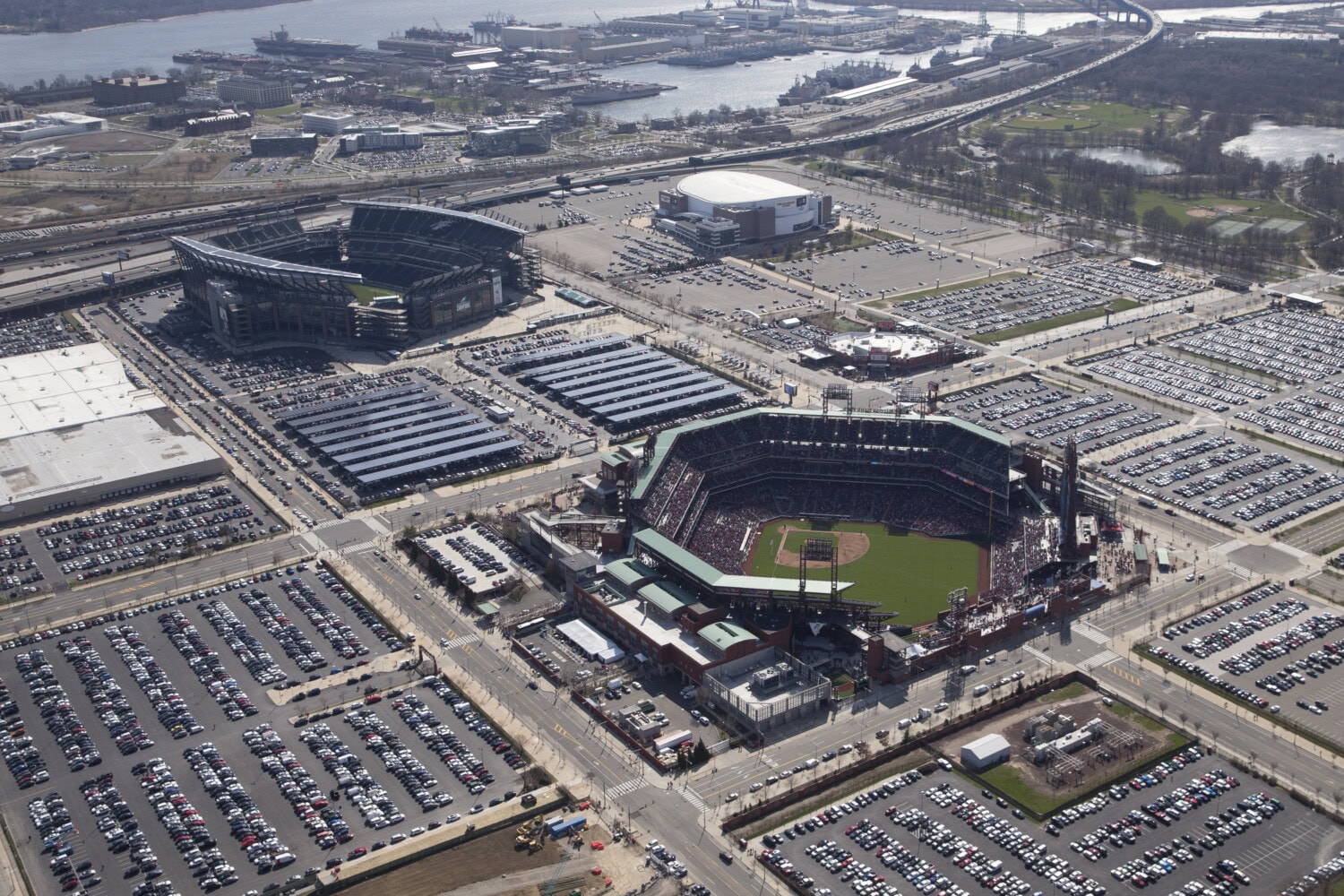

The Wells Fargo Center opened in 1996 at the South Philadelphia Sports Complex on Broad Street. Veterans Stadium housed the MLB’s Phillies and NFL’s Eagles, while the 21,000-seat sequel to the iconic Spectrum — formerly known as the CoreStates Center, First Union Center, and Wachovia Center — hosted the NBA’s 76ers and NHL’s Flyers. Lincoln Financial Field opened in 2003 for the Eagles and Citizens Bank Park opened in 2004 for the Phillies, leaving Wells Fargo as the Sports Complex’s oldest arena.

Comcast Spectacor, the sports and live entertainment division of media conglomerate Comcast, owns Wells Fargo Center and the Flyers. It also owned the Sixers until 2011, when it was sold to a group led by Josh Harris and David Blitzer for a reported $300 million. Forbes recently estimated the 76ers’ current value at $3.15 billion.

While both Citizens Bank Park and Lincoln Financial Field are owned by the city, the Sixers have been the only major professional sports franchise in Philadelphia that are tenants to owners of a different team. The 76ers say being a tenant puts the team at a competitive disadvantage, choosing dates for home games after the Flyers and various shows and concerts get their pick. It probably also doesn’t help that Harris Blitzer Sports & Entertainment also owns the New Jersey Devils, the Flyers’ NHL division and geographic rival, and has to pay rent to the owner of its hockey adversaries.

Sixers minority stakeholder David Adelman pointed to the team’s March schedule that featured what he called a brutal five-game road trip in the month’s first seven days and just five total home games as a direct result of not owning its venue.

“We’re a third choice,” Adelman told Boardroom as part of our in-depth series on the Sixers’ arena plans. “We’ve only had one Christmas game in 11 years. We’re away because “Disney on Ice” is here. We have more back-to-backs and five-out-of-seven nights than anybody in the league. We want to control our own destiny.”

So, with the Sixers’ lease expiring in 2031 at Wells Fargo Center, the team has already said it will not be re-signing. Rather, it’s pursuing a new arena in the Center City district away from the Sports Complex called 76 Place, spearheaded by Adelman, which would open in time for the 2031-32 NBA season.

When landlords and tenants don’t see eye to eye, however, things can get contentious.

That’s certainly going on behind the scenes between the Sixers and Comcast Spectacor.

One local business leader went so far as characterizing Sixers-Comcast Spectacor arena interactions as a “war.” In an email to Boardroom, Comcast Spectacor called this characterization inaccurate, stating that the company greatly values its relationship with HBSE, has nothing but respect for them, and is excited about and bullish on the future of what it called the new Wells Fargo Center and the Sports Complex.

Comcast Spectacor considers Wells Fargo Center a new, world-class arena thanks to a $400 million privately funded renovation including a new club level, an overhauled main concourse, upgraded suites, and other building-wide improvements, with further plans to develop the South Philly Sports Complex into one of the country’s top sports and entertainment destinations — but a quirk in the 1996 arena lease put the responsibility to renovate and improve the Sixers’ team facilities inside Wells Fargo Center on the tenant rather than the landlord.

“We felt like we really needed to do something to get the team areas here up to even close to an NBA standard,” HBSE and 76ers CEO Tad Brown told Boardroom. Before a late March game against the Dallas Mavericks, the Sixers unveiled a completed new locker room, weight room, training, rehab, and other facilities as part of a $9 million upgrade for which they footed the bill.

“This is a unique lease situation that made it part of the team’s obligation,” Brown said. “We abide by our lease. We appreciate the changes Comcast made.”

Notably, Comcast owns not just Wells Fargo Center, but also NBC Sports Philadelphia, which broadcasts the Sixers’ local games with a contract running through September 2029. The business relationship will endure despite the two sides’ differences; Comcast Spectacor said it will continue to be a great partner to HBSE and the 76ers whether they extend the lease beyond 2031, otherwise partner on the renovated current arena, or succeed in building their own.

“We want a good working relationship with them. We share the facility and we’ll continue to do that,” David Adelman said of the Comcast relationship. “One thing should have nothing to do with the other. I think they’re doing a nice job with the TV rights. We’ve had very open and transparent dialogue with them about our intent, and they’ve had open dialogue about theirs.”

Adelman pointed out that Wells Fargo will be one of the NBA’s oldest facilities by lease’s end with sightlines built for hockey, not primarily for basketball. HBSE invited Comcast Spectacor’s Flyers to join the Sixers in 76 Place in 2031 — something the team said Comcast seemed somewhat receptive to initially — but the company’s current stance is that it’s committed to and believes in its current home and the broader Sports Complex moving forward.

Further, an additional sports arena would likely cut into Comcast Spectacor’s annual revenue, but many in the 76ers camp believe that a major city like Philadelphia is big enough to support two top-quality indoor venues.

“They can both still live well from an entertainment perspective,” Adelman said. “Whoever we’ve spoken to are ready for a newer, better option for their talent and we think we can accommodate that.”

When asked whether there was concern that a new arena would significantly impact Wells Fargo Center’s ability to generate revenue and profit, Comcast Spectacor said it’s extremely excited and optimistic about the future of its world-class arena in a growing sports and entertainment district at the Sports Complex.

Amid the intrigue, Boardroom spoke to someone who knows better than almost anyone about live entertainment venues: Irving Azoff. The Rock and Roll Hall of Famer and legend of the music and entertainment industry said he supports the trend of NBA teams building downtown arenas and investing in additional entertainment options around such venues to provide fans a plethora of options to improve the game day experience.

“They want hotels, restaurants, bowling alleys, movies, Top Golf, massive restaurant options,” Azoff told Boardroom. “Every one of these downtown places is becoming like a mini Las Vegas. The future inevitably to me is if you’re given a choice, put your arena downtown. As much as I hate to admit it, the Staples Center revitalized downtown LA.”

As co-founder of stadium developer Oak View Group and a veteran of the music industry spanning more than 50 years, Azoff knows that booking dates for premier musical acts is difficult in arenas that host more than one pro sports team. All the weekend dates get eaten up, and NBA and NHL teams have holds on dates for two months during the playoffs. Azoff cited internal research estimating that there are 12 or 13 shows at Philadelphia’s baseball and football stadiums, 40 at the Freedom Mortgage Pavilion in nearby Camden, New Jersey, 10 to 15 at the Mann Center for the Performing Arts, and 40 to 50 at Wells Fargo.

“Philadelphia is a vibrant, big market that should be bigger and would be bigger [with a second arena],” Azoff said. “Through Oak View Group, we consult a lot of basketball teams and we’re landlords to hockey and basketball teams. When a lease runs out for an NBA or NHL team and they stay in an arena, even if they were to stay, the landlord wouldn’t make the kind of money on a new deal that they currently make. That’s just the way the business runs.”

The Sixers are in a similar boat as the Los Angeles Clippers, who are currently tenants alongside the Lakers, the WNBA’s Sparks, and the NHL’s Kings at downtown LA’s Crypto.com Arena while they build their own venue, Intuit Dome, slated to open next year in Inglewood. Azoff said it wouldn’t be a huge loss for Crypto.com Arena when the Clippers leave because the team doesn’t pay much in rent; he would even argue the arena could make more money through additional concerts than holding 40-plus Clippers home games.

“Just opening up those nights up so if they could play more music, they can make it up easily,” Azoff said. “Honestly, if you don’t own the team and you’re just the landlord, one night of music is far more profitable to an arena than one night of basketball.”

One member of the news media in Philadelphia who requested anonymity in order to speak freely noted to Boardroom that Comcast told them and others that there just wasn’t enough consumer demand to support two Philadelphia arenas, thus they are heavily lobbying in opposition to 76 Place. This person understands that Comcast doesn’t want to lose the Sixers’ business, but as the previous owners of the franchise itself, they said that Comcast should have seen this scenario coming after selling to Josh Harris and David Blitzer’s group in 2011.

When Boardroom asked if Comcast Spectacor regrets selling the Sixers, the company stated that it continues to be a great partner of the team and will continue to do so whether they build their arena or not.

The news media member said they’re disappointed when they hear people saying the Sports Complex would have better SEPTA public transit access than the proposed Center City arena atop Jefferson Station because they know the talking point came from Comcast Spectacor. A train along the orange Broad Street line isn’t a convenient trip for most people, the individual said, while the new arena with regional rail access to two million people in the greater Philadelphia region would provide value for fans who wouldn’t have to bother with traffic and parking.

The news media member called Philadelphia a company town in a sense, and that company is Comcast. It’s one of the largest employers in the city and one of the last locally based companies that hasn’t been merged with or acquired by a different conglomerate. Comcast Spectacor said that the company employs 11,500 people in Philadelphia and doesn’t expect a new Center City arena to have an impact on its workforce.

“This is adjacent to their workforce. I actually thought they’d be excited,” Adelman said. “I’m giving their employees something to do when it’s so hard to get people back to work.”

A lot of local residents, the news media member believes, feel obligated to Comcast, which is very integrated into the local ecosystem. The Sixers may have underestimated how much hold and reach Comcast Spectacor and its parent company have.

Following its acquisition of NBC Universal from General Electric in 2011, Comcast’s influence extends to the NBC family of networks, which are viewed by millions each week between television and streaming. In late April, the 76ers received emails from NBC’s prime news program, NBC Nightly News, as well as from financial news network CNBC requesting comment for a story for the company’s digital platforms on challenges involving Chinatowns across the country, including the proposed 76 Place near Philadelphia’s own Chinatown, that was to look into how urban Chinese diaspora communities have been combating gentrification and protecting their culture and history amid the rise of luxury developments. May was Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month across the United States, which brought the subject into an even brighter spotlight.

A second local media member more specifically connected to the local sports scene said that the 76ers and Comcast Spectacor have been on the phone with anyone they could get ahold of to convince them to take their side in this arena battle, trying to generate any amount of leverage they can muster. Comcast Spectacor has a lot to lose if the Sixers leave, this person said, especially after spending $400 million of its own money on Wells Fargo Center upgrades. A tenant would immediately become a competitor as soon as a new arena opened.

This sports media member believes that Comcast Spectacor is sensitive about this issue in part due to the threat of the Sixers taking top musical acts and other in-demand events with them, but that the company shouldn’t worry too much considering that Wells Fargo Center does well currently against other local and regional competitors.

Comcast Spectacor said it would love to negotiate a new lease with the 76ers that would allow them to purchase some manner of equity in the building itself. It believes the future of South Philadelphia is incredibly bright and that it would love for the Sixers to be a part of that story.

For its part, a 76ers spokesman said that if the team doesn’t have the necessary approvals for the current Center City project by the end of the calendar year, they would be faced with a decision on whether to proceed with buying a separate piece of land at the Fashion District Mall site to the east. The team believes Comcast knows this, which is why they’re trying to delay the approval process as much as possible.

Another major part of the approval process? Working closely and productively with community groups across the city. And as we’ll see in Part III of our Boardroom series, many of these groups find themselves deeply divided when it comes to the 76 Place proposal.

Stay tuned for the next story in our series, which will cover the discourse between Philadelphia community groups with differing views of opinion regarding 76 Place.