The film updates Stephen King’s dystopia with a surveillance-heavy world that feels familiar, but the story’s rhythm doesn’t always rise with the stakes.

Edgar Wright’s The Running Man arrives at a time when the idea of entertainment as surveillance doesn’t feel like fiction.

Stephen King set this story in 2025 in the original novel, which was published in 1982 under his pseudonym, Richard Bachman. The year finally caught up, and Wright leans into that convergence with a high-velocity remake. The film has scale, ambition, and a sharp sense of the world it wants to critique, but the execution doesn’t always match the intent.

Synopsis & First Impressions

The film follows Ben Richards (Glen Powell), a blue-collar father from the impoverished “Slumside,” where medical care is scarce, jobs are unstable, and corporations control every aspect of survival. When Ben’s toddler becomes sick and he loses yet another job for insubordination, he’s pushed into the Network’s slate of violent game shows. The crown jewel is The Running Man, a month-long televised chase where contestants must outrun state-backed hunters for 30 days to win $1 billion and a spot in the top 1 percent of the country’s wealthiest individuals.

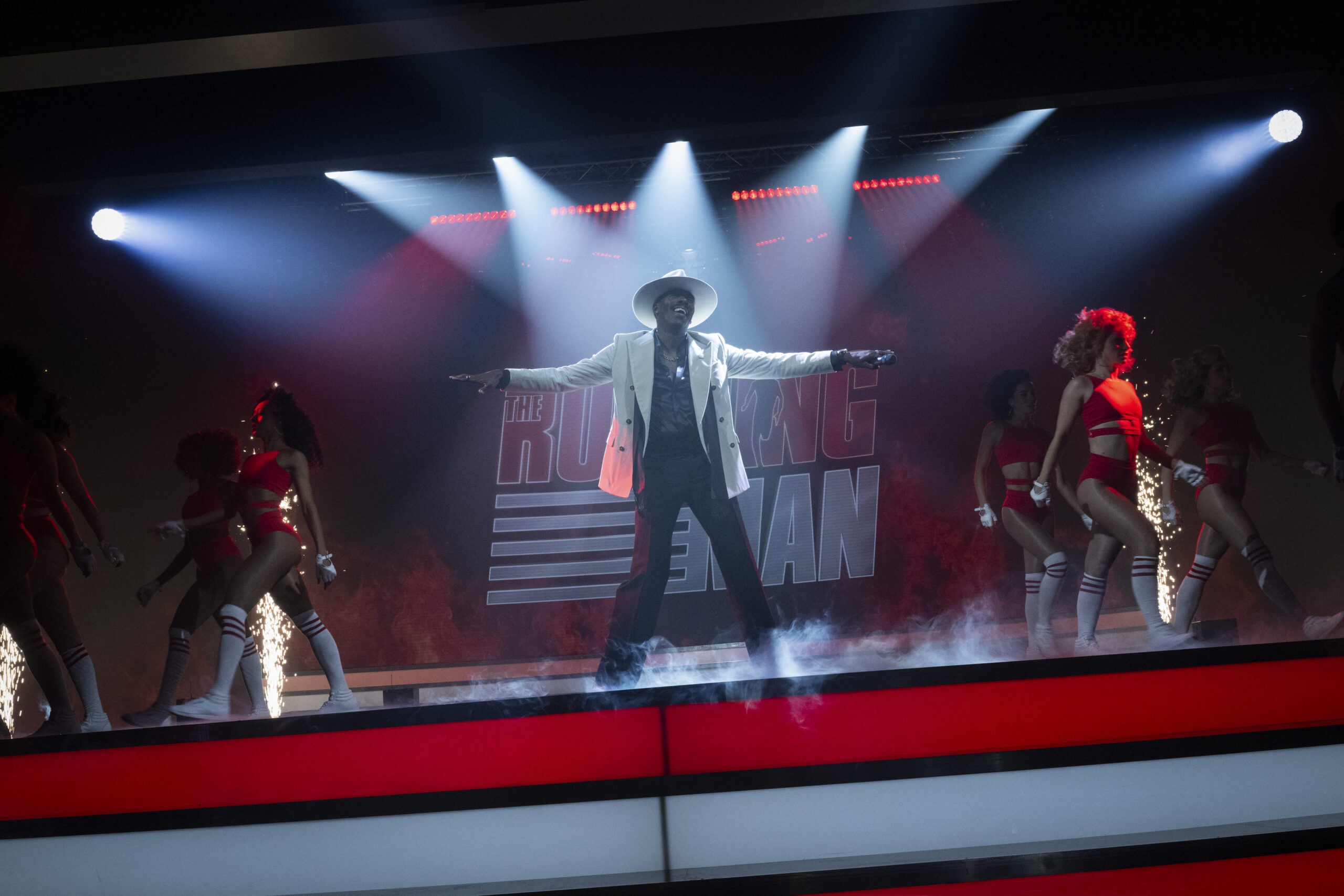

Slumside feels starved of resources — down to something as small as socks — while the Network’s production floors are glossy, oversized, and steeped in corporate dread. The film tracks Ben from the moment he signs up for the show. Cameras sit everywhere throughout cities to track the hunt, and the show’s host Bobby T. (Colman Domingo) is part ringmaster and part propagandist, and audiences at home are offered prizes to turn runners in.

The arenas aren’t sealed-off stages this time; the “game” unfolds across real cities, with citizens acting as informants or allies. The shift is effective. It widens the scope and makes the world feel unstable in a way the original film never attempted to do. That version, led by Arnold Schwarzenegger in 1987 alongside María Conchita Alonso, Yaphet Kotto, and Richard Dawson, reimagined the story as a campy, enclosed gladiator spectacle with exaggerated stalkers and choreographed set pieces.

Wright’s remake moves closer to King’s 1982 novel, embracing the book’s bleak social structure, its open-world chase across multiple cities, and the idea of the public directly participating in the hunt. It replaces the neon, game-show sheen of the ’87 film with a colder landscape of corporate control, media distortion, and everyday people choosing whether to help or betray a runner. Where the original leaned into satire and theatrics, this version expands the geography, raises the stakes, and shows a society far more complicit — and far more recognizable.

Visually, the cinematography is coarse and shadowy, set against crowded streets, rundown buildings, and the constant presence of surveillance. The action is physical and unpolished by design; you feel the strain of Ben’s run as the days stack up. Some sequences hit with genuine tension, but the film settles into a pattern in the middle stretch. The cycle of chase, escape, and reset starts to blur, and the emotional stakes don’t always rise at the same pace as the physical ones.

Wright’s attempt to merge King’s bleakness with his own signature energy doesn’t always resonate. At times, the movie feels pulled between satire and a straight-ahead thriller. It’s entertaining, but the commentary doesn’t consistently land with weight.

Performance Check

Powell anchors the film as Richards, carrying the majority of the physical and emotional weight. His performance leans into the exhaustion built into the story; the running, hiding, and improvising all feel strained in a way that serves the character. Powell works best in the grounded moments tied to Ben’s family, where the stakes sharpen and the noise drops. The script doesn’t give him a complete emotional arc, but he keeps Ben human even when the story pushes him into constant motion. However, in the more heightened or frustrating moments, his delivery drifts toward satire in a way that doesn’t always align with the film’s darker tone. It’s not a misstep, but it adds a layer of exaggeration that feels at odds with the grounded world Wright is trying to build.

Daniel Ezra brings a needed pulse to the film as Bradley Throckmorton, one of the few characters driven by belief rather than survival. In our conversation, Ezra told me Bradley believes in a better world that never wavers throughout the movie. That conviction shows. Bradley’s presence becomes a counterweight to the Network’s cruelty, and Ezra plays him with a warmth that cuts through the film’s bleakness. He also said playing Bradley was inspiring and that it’s always nice to play characters that inspire him. That connection is visible. His scenes add dimension to the story’s politics and give the film a spark of optimism it wouldn’t have otherwise.

“It doesn’t happen all the time, and it shouldn’t happen all the time, but getting to play a character that I think in the real world I would probably look up to and admire was so much fun,” Ezra said. “Right now, for good or bad, feels like the perfect time for a movie like this.”

Domingo delivers one of the film’s most memorable turns as Bobby T., turning the host role into something charming and predatory at once. He treats every broadcast like a performance designed to distract the audience from the violence he’s guiding them toward. Josh Brolin plays Dan Killian with cold composure, though the screenplay keeps him more functional than layered. And while Lee Pace’s Evan McCone has a compelling setup — a former contestant forced into the role of hunter — the film doesn’t give him enough space to explore it. Still, watching Pace’s character unfold was a treat.

Jayme Lawson adds depth to the emotional layer of the film as Sheila, Ben’s wife and the mother of his child. Her work is subtle, grounding the story in lived-in intimacy rather than melodrama. Lawson spoke about how she and Powell spent time shaping the relationship of their characters before circumstances hardened around them.

“We spent a lot of time really crafting our chemistry, but more so figuring out who they were before they had this kid,” Lawson told Boardroom. “So when we step into these circumstances with a crying child, a sickly child, and things aren’t getting better, you can still feel there’s real love between them — that they’re doing this with each other, not against each other.”

That work shows in her performance. Lawson was drawn to how the script expands Sheila beyond the version in the original material, giving her a fuller presence and a life outside Ben’s arc. That added depth strengthens the film’s emotional stakes and keeps the story from relying solely on its spectacle.

Final Thoughts

The Running Man is ambitious and visually strong, with a world that feels close enough to our own to be unsettling. Wright honors King’s original ideas about media manipulation, inequality, and public appetite for violence, even if the film isn’t sharp enough to cut through all of them.

Still, there’s value here. The cast gives the story heart. And the movie isn’t afraid to interrogate what a corporate-controlled entertainment machine can turn people into. Some of its commentary gets muddled, but the core message lands: a single person can’t outrun a system built to consume them, but a collective might.