Exploring the craft, the marketing, and the money that went into Dr. Dre and Snoop Dogg’s 1999 comeback classic — and everything that’s come out of it since.

Recently, Spotify’s RapCaviar playlist ranked the beat from Dr. Dre’s “Still D.R.E.” as hip-hop’s best ever.

As we celebrate a half-century of rap music this year, the lead single off Dre’s timeless 2001 remains a masterclass in composition, pairing Scott Storch’s staccato-style piano with mixing and mastering from the good doctor himself.

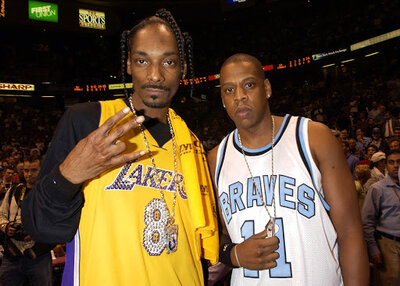

A California classic, the Snoop Dogg-assisted song released in 1999 still — as its title is apt to remind us — strikes a chord, as it’s streamed over 1.1 billion times on Spotify alone.

But what if we told you “Still D.R.E.” almost never happened?

Coming on the heels of label litigation, famous fallouts, and consecutive flops, many movers and shakers within hip-hop had the former Death Row co-founder left for dead.

Instead, Dre revived his career by bringing in a new business partner from the rock and roll industry while aligning with collaborators from a rival coast.

Having since sold his catalog for over $200 million, Boardroom breaks down the business behind the comeback classic that still earns today.

“Ladies and gentlemen, Tupac Shakur!”

On Feb. 17, 1996, Tom Arnold introduced rap’s resident bad boy to a salivating Saturday Night Live audience.

Playing the ultimate away game during the height of the East Coast vs. West Coast beef, the icon once known as MC New York rhymed aggressively on stage in an oversized khaki shirt backed by a live band and Zapp frontman Roger Troutman.

He was there to support All Eyez on Me, a double album released only days prior on its way to going Diamond.

Relishing the moment, he performed the project’s first single, “California Love,” with Troutman in tow.

Dr. Dre was nowhere to be found.

Despite producing and appearing on the 2Pac track, the Compton composer was working feverishly behind the scenes to leave the label he co-founded with Suge Knight only five years prior. Despite boasting three Platinum albums on the charts and two more on the way, the house he built was becoming both treacherous and toxic from within.

“I made a few mistakes picking the people I wanted to do business with,” Dre told MTV News in 1996, “but I consider those positive mistakes because I learned a lot from those mistakes.”

On March 22, 1996, it was done: Dr. Dre announced he was leaving Death Row Records and forming Aftermath Entertainment.

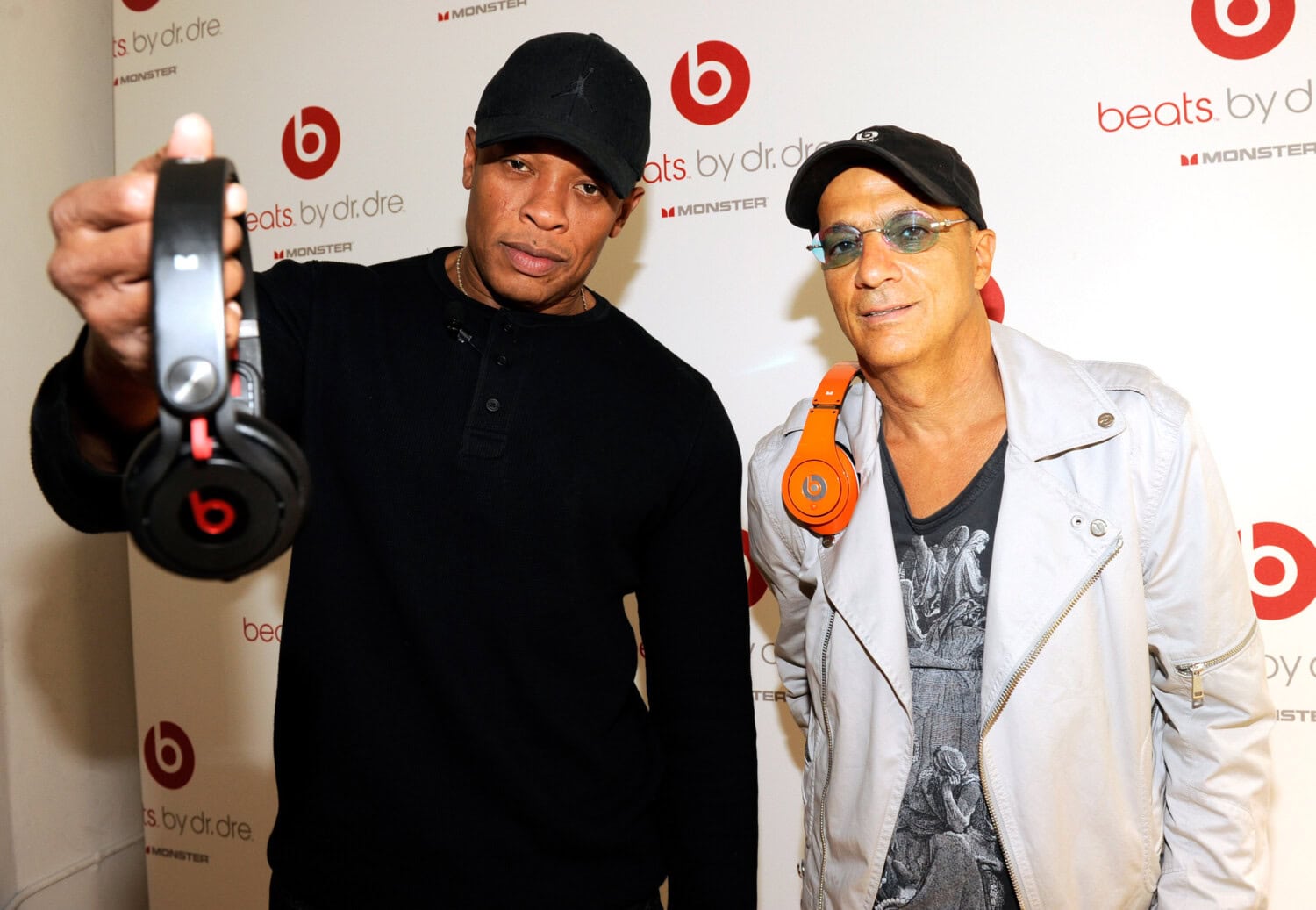

Operating as a subsidiary of Interscope, it allowed Dre to get out of Knight’s dark and dangerous shadow while learning new intricacies of the business from prolific producer-mogul Jimmy Iovine, the parent label’s co-founder.

While 2Pac may have been promoting “I Ain’t Mad at Cha” on SNL, trust, you didn’t want Suge Knight mad at you.

Regardless of Death Row already having an exclusive distribution deal with Interscope, the move for Dre was far from free and fresh air. Going against Suge meant being constantly marked and haunted by the possibility of physical violence, image attacks, and uncertainty about one’s ability to collaborate with several other top artists due to label politics.

For financial reasons — as well as the power Suge wielded across California — Dre’s departure from Death Row was as risky as it got.

Perhaps it would have been more dangerous to stay.

To Live & Die in LA

On Sep. 13, 1996, Tupac Shakur was pronounced dead in a Las Vegas hospital.

Famous for wearing UNLV gear upon his solo arrival, rap’s most spirited superhero had been shot on the strip not far from where the Runnin’ Rebels hosted home games. Rolling with Death Row saw Pac literally gambling with his life, making Dre’s departure all the more prophetic.

“I feel like the gangster rap era is over,” Dre told MTV News in 1996. “Been there, done that, it’s time for something else. You can’t use profanity on a record and sell millions. You have to come with some skills and you have to come with some substance whether it be tracks or vocally.”

Prior to Pac’s passing and soon after leaving Suge’s shadow, Dre made good on his pivot by producing Blackstreet’s “No Diggity” alongside New Jack Swing impresario Teddy Riley.

Also on Interscope, the R&B group and the song’s soaring success proved the prophecy of just why Dre left Death Row and gangster rap behind.

However, Dre’s success infuriated his previous peers. In short order, Pac was sending shots at Dre over an altered version of the Blackstreet single on “Toss it Up.”

No matter how far he got away from Death Row, danger followed Dre — but would success?

Dre had back-to-back No. 1 hits on the radio despite how rocky the road was. As expected, there was more money in clean records that could reside on FM stations and move massive units.

Dre was rolling. And then, the momentum stopped.

On Nov. 26, 1996, Dr. Dre released Dr. Dre Presents: The Aftermath, a compilation album stamping a new label and a new direction.

Dropping at a time when “No Diggity” was still atop the charts in America, it missed the mark with the hardcore consumers who had supported him since his N.W.A. days while also failing to find crossover appeal.

In a sense, he’d flipped the Bad Boy formula of shiny sample-driven songs, inverting it in eery, smoked-out styling. The problem was it lacked both the fun and star power of what Puff Daddy’s Bad Boy Records was producing out East.

No need to worry — Dre had connections, ideas, and respect.

Eleven months after the Aftermath compilation, Dre extended his services to The Firm — a supergroup led by Nas intended to bridge coasts and lanes. Instead, a lack of continuity and poor promotion doomed the project.

Considered a colossal flop for the potential of its parts, Dre was sitting on back-to-back bricks since starting his label.

Entering 1998, Andre Young was at rock bottom. He wasn’t alone.

The Reunion

1997 was not kind to Dr. Dre. It was very good to Master P.

After a college hoops career that started in Houston with Hakeem Olajuwon, New Orleans native Percy Miller made a name for himself in California by opening No Limit Records and Tapes thanks to money from a medical malpractice settlement he inherited following the death of his grandfather.

In the early ’90s, the New Orleans entrepreneur would parlay his store income into a rap career of his own. Working a crowd came naturally to Percy; he opened up for 2Pac as an amateur before making his own label legit.

By 1997, No Limit and P were as limitless as it gets, moving with more momentum than Death Row — and with less drama.

From CDs to movies, the 504 mogul had the streets and the suburbs consuming all of his output. The money was pouring in bolstered by album art and music videos that reflected Master P’s rags-to-riches rise.

And with cash flow comes the power to pull others out of dire situations.

In 1997, Snoop Dogg was stuck.

“Death Row wanted to kill me,” Snoop told the “85 South Show” podcast in 2022.

With Dre gone, 2Pac dead, and Suge Knight headed to jail, Snoop’s spirit was broken even if he had two No. 1 albums to his name. While working on his sophomore effort, the strong arm of Suge kept him from collaborating with Dre, robbing the smooth songwriter of his best beatmaker.

He’d beat a murder case, but musically, he needed a hero. Suddenly, Master P was a power player who could sign Snoop Dogg away from Suge’s clutches.

It couldn’t have come at a better time.

“Death Row showed me the show; Master P showed me the business,” Snoop said. “So now, I’m the king of show business. No Limit was a three-year college run for me. P was serious about his business.”

In short order, Snoop was getting paid publishing checks for appearing on an array of No Limit projects while producing his own. He was free from the drama with a new lease on life and property in his name.

Though working with No Limit’s Beats by the Pound production team put the Doggfather in a whole new sonic space, it was always Dr. Dre that brought out his most crisp and consistent work.

With P pulling the strings and Suge locked up, the Cali kings could ride again.

Finally having distance from Death Row and assistance from P, the two reunited on “Bitch Please,” a return to form made to feed their West Coast fanbase with no regard for radio.

After two years of flops, Dre was back in his groove. So was his old buddy.

Thankfully, Dre had just signed a new friend, too.

While Dre’s former business partner was famous for dangling white rappers over hotel balconies, his new partner saw an opportunity in outsiders. In March 1998 — the same month Snoop signed with No Limit — Aftermath inked Eminem: a battle rapper from Detroit who had only sold 1,000 copies of his debut album, Infinite.

Leaning into Eminem’s sadistic alter ego, Dre shocked the world by producing and appearing on 1999’s The Slim Shady LP. Unlike each artist’s previous outputs, the Aftermath album went 5x Platinum in the US alone.

In Eminem, Interscope’s new subsidiary was set. Iovine and Dre finally had an MC as compelling as Ice Cube and as charismatic as Snoop.

With the Aftermath engine behind him and the ultimate hip-hop co-sign, the trailer park talent was instantly an international superstar, fueling the fire for Dre to take center stage again.

“For the last couple of years, there’s been a lot of talk out on the streets about whether or not I can still hold my own,” Dre told The New York Times in 1999.

Considering the Aftermath and Firm albums, who could blame them? Reinvigorated, Dre began writing and recording for a year and a half. That process culminated with 2001: a comeback album of sorts originally intended to be a mixtape.

He claimed his motivation was doubt stemming from magazines and rap tabloids. However, it was old colleagues who were also sending sparks.

In May 1999, Death Row responded to Dre and Slim Shady’s success. They called it Suge Knight Represents: Chronic 2000.

Playing off the 1992 Dr. Dre album title Death Row still owned, the compilation was a way to raise old tension, stringing together unused 2Pac vocals and leading the rollout with an Eminem diss as the album’s first single. While the project flopped, its intended targets remained miffed and motivated.

Back in Burbank, Dre was busy mining rhymes from Em and Xzbit while building beats with Lord Finesse and Mel-Man.

All the while, Death Row remained on his ass and the sounds of nu-metal were dominating the charts.

Undeterred by old beef or new styles, he dug deep to make the true Chronic sequel fans had been waiting on. In a matter of months, the album was done, with “The Next Episode” featuring Snoop Dogg and Nate Dogg set to lead the way on the airwaves.

Despite being somewhat green to hip-hop, Dre’s new business partner had other ideas.

“You need one more song,” Iovine recalled in the 2019 HBO docuseries The Defiant Ones. “I will lay down on the street in front of these trucks before we let that go first.”

In Iovine’s mind, “The Next Episode,” whose key sample smacked of avant-garde jazz cat David Axelrod, was not to be the first. Already sharing studio space with rap royalty from up and down the West Coast, Dre phoned in a favor from Philadelphia’s famous Roots crew to provide new energy to finish the album.

But it wasn’t Questlove, the drummer who was working diligently on D’Angelo’s second album, nor was it Black Thought, an MC revered as one of the strongest writers in the game.

Rather, it was a high school dropout who hated touring but loved the keyboard.

The Piano Man

Scott Storch was kicked out of his house at age 16 but welcomed into Dr. Dre’s studio with open arms.

“I went to Dr. Dre University,” Storch told the “Drink Champs” podcast in 2022. “I learned so much.”

The son of a singer and nephew to a songwriter, Storch was a music man down to his DNA that loved to produce far more than perform.

A chance trip to Los Angeles and a run-in with fellow Philly artist, Eve, led to an introduction to Dre as the femme fatal from the Ruff Ryders was already working with Aftermath.

“I knew Scott from Philly from the time I was about 14 or 15,” Eve told Boardroom. “He happened to be in LA at a time when I was signed and I invited him to come to a session.”

Just as Storch was passing through Cali, Dre was working night and day trying to find the sound to finish his new album and introduce it to the public per Iovine’s insight.

“Me, Dre, Mike Elizondo, and Mel-Man were all beat mining,” Storch said. “We were searching for the best fucking beat and Dre’s standards were so high. The 2001 album was legendary, everything on it. Dre has all this fire and he’s looking for the first single.”

Sifting through upwards of 100 hot tracks, Dre programmed a drum pattern he was keen on while Storch plugged away on his keys.

“I was thinking all night about some piano piece that’s wrong but right where it’s kind of off-beat,” said Storch. “It kind of went with that drum pattern.”

Well, more than kind of.

“Dre ran in the room,” said Storch. “‘That’s it! That’s the fucking thing right there!’ We went to work immediately.”

From there, Storch’s staccato piano play evoked the eery and emotional chord Dre was looking to strike, playing perfectly off the programmed drums. While Dre is long known for having one of the best voices in hip-hop, his ear for sound and eye for talent are likewise unmatched.

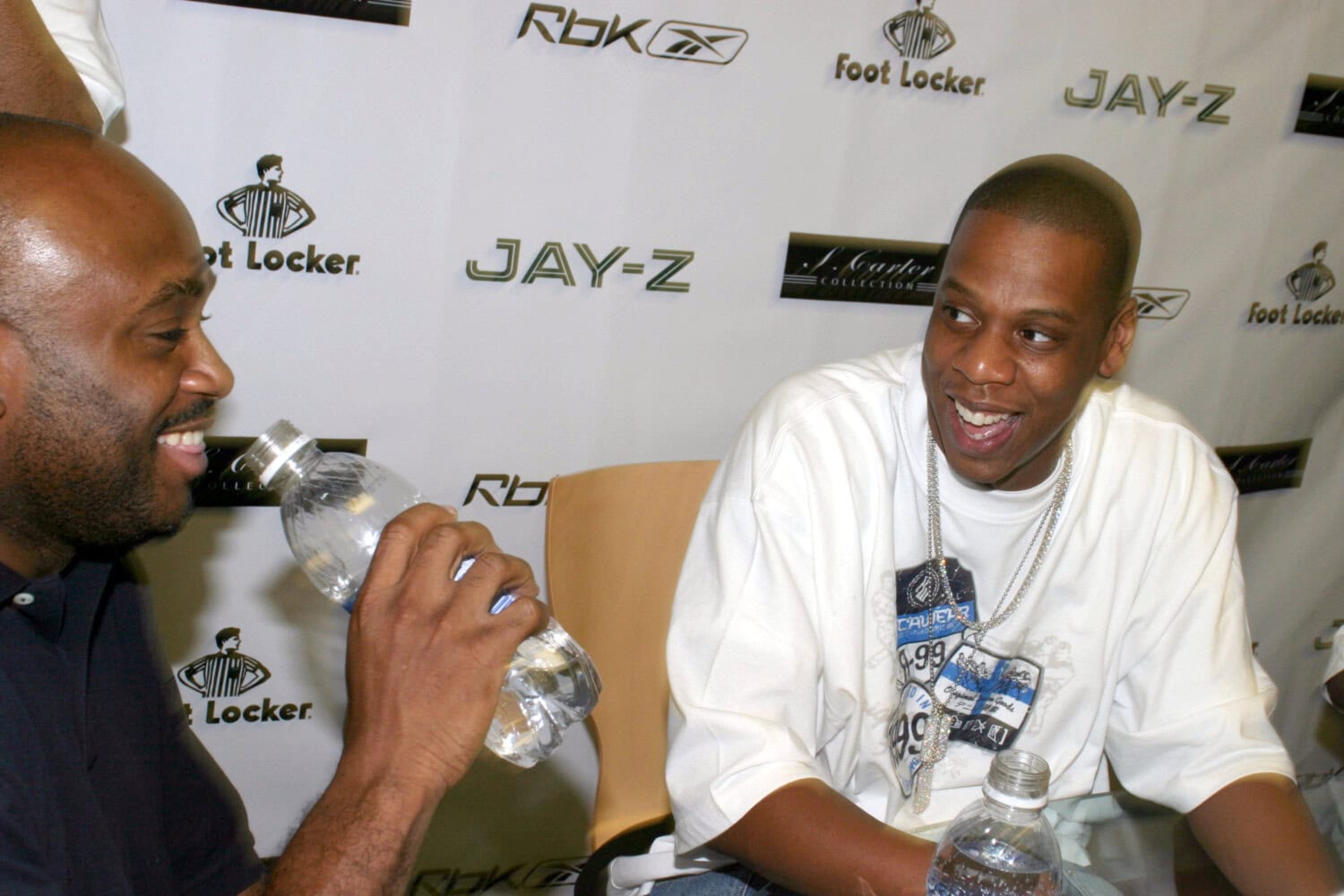

“His radar is impeccable,” Storch said. “I probably played him 50 things that day but he came in and said, ‘That’s it right there.’ The track was done in 20 or 30 minutes. Dre said, ‘I’m going to send this to Jay-Z and we got one.'”

The Hand That Don’t Write

By 1999, Shawn “Jay-Z” Carter had been in the game for years. It made him an animal.

Aside from his own catalog of Platinum albums, the Roc-a-Fella co-founder had the ability to shift shape and form, writing rhymes for everyone from Foxy Brown to Bugs Bunny. It wasn’t a talent he advertised; it also wasn’t money he turned down.

“I never shop myself to write for people, I’m just here,” Jay told MTV News in 1998. “I don’t write anything and not use it, either.”

Prior to putting out 2001, Dre had crossed coasts thanks to his work with Nas on The Firm’s 1997 LP, The Album. While the project may not have gained the critical or commercial success expected of it, it did put Dre in close contact with Steve Stoute.

Stoute, then in-house at Interscope as an Executive Vice President, was from New York but brokering deals from East to West.

The industry exec was as savvy as it came when working every angle of potential, placing Nas in a more mainstream lane while also getting the Queens scribe paid properly as a ghostwriter for the likes of Will Smith and Kobe Bryant.

Across the country, Dre had everyone from Eminem to Royce da 5’9″ writing raps for 2001. Still, there was only one person fit for penning the album’s introductory single.

“Dre knew he wanted to put Jay-Z on it,” said Storch. “Xzibit was in the studio trying to write some shit to it. It was cool, but it wasn’t exactly what Dre wanted.”

From there, the urban legend of the song’s structure grows. Some say the verse came in a matter of minutes while others allude it was a matter of sun up to sun down.

“It was almost immediate,” Storch says. “The vocals came back and Jay-Z’s demo version of that shit was insane.”

“On that reference track I’m doing Dre and Snoop’s vocals,” Jay said on HBO and Uninterrupted’s The Shop in 2021. “The reference track sounds like them.”

“He wrote Dre’s shit and my shit and it was flawless,” Snoop told The Breakfast Club in 2020. “It was ‘Still D.R.E.’ and it was Jay-Z. He wrote the whole fucking song.”

“Jay Z wrote those lyrics,” Dre said in The Defiant Ones. “I think they came back in maybe 24 hours with the whole song written.”

Perhaps difficult does take a day.

While the collective heads of Dre and Storch spent what felt like forever mining for the sound of the album’s first single driven by Iovine’s insight, the creation of the song itself was cosmic in conception once the New York rapper found himself writing for the West Coast kings.

“The music that they were making and The Chronic and all that? It had to be a studied reverence of what they were doing,” Jay said.

“Jay-Z is a great writer to begin with for himself,” Snoop said, “so imagine him striking it for someone he truly loves and appreciates. He loves Dr. Dre and that’s what his pen showed you — that I can’t write for you if I don’t love you.”

From there, the single was pressed. Bad blood from rap rivalries was not deeper than art, nor more important than moving units. But even if the vibes were immaculate across the country and inside the studio, challenges did lay ahead.

Dre, Iovine, and Aftermath had to prove their power all over again.

The Rollout

Leading an anticipated album with the wrong first single could doom a project in the 1990s. Case in point: Dre’s recent misstep with The Firm only two years prior.

Rather than lead with his eery introduction to mafioso rap, “Phone Tap,” the label led with the En Vogue-assisted “Firm Biz”: a radio reach that killed all credibility critical to a crime classic, making the blockbuster cast of Nas, Foxy Brown, AZ, and Cormega catch criticism and the physical CDs catch dust.

“Do you know how many people would have ran out to buy that album if the first thing they heard was that song?” producer Chris “The Glove” Taylor told AllHipHop in 2012 in reference to “Phone Tap.”

He wasn’t wrong.

Neither was Iovine.

Having produced records for all-time rockers like Bruce Springsteen and Tom Petty, Iovine possessed an unorthodox ability to know just what type of sonic honey would create the right buzz around an album.

Keep in mind that for decades, fans had to purchase a whole project for $10 to $20 rather than just freely stream individual songs.

For this reason, “Still D.R.E.” was released in music video form on Oct. 3, 1999, so the world could see the dynamic duo free from Death Row riding again. For the first time in years, everything felt right. Even SNL was calling.

“The greatest promotion man is the one with the best record,” Iovine said in The Defiant Ones.

While the target audience on paper for “Still D.R.E.” may have seemed like California which Iovine and Dre called home, it was still the Big Apple’s cultural gravity that moved the masses.

Only two years removed from the murders of The Notorious B.I.G. and Tupac Shakur, one had to wonder just how much grace two rappers adjacent to the Death Row drama could get on the East Coast.

No longer in Burbank with his Westside connections, Scott Storch wondered, too.

“I was driving from Philly to New York,” Storch said. “Funkmaster Flex? That motherfucker dropped bombs on ‘Still D.R.E.’ for 45 minutes before one vocal was in there. I’m sitting there frozen up stuck on the bridge and I was happy as shit. The song finally started playing as I made it to the Holland Tunnel.”

Despite the tremors and aftershocks of those coastal tensions, Dre and his camps already had inroads into the most influential DJ in NYC.

In 1998, Mel-Man had a placement on Funkmaster Flex’s The Mix Tape, Vol. III, standing out in a sea of Yankees caps.

A year later, the track Mel co-produced with Dre and Storch was now a radio mainstay on New York’s Hot 97, with only those in the know realizing that Jay-Z wrote it. It was a moment for all involved, especially the East Coast resident who played the piano Flex had on loop for nearly an hour.

“I think I’m gonna be a big fucking record producer,” Storch said, “because I knew how impactful that record was when I heard 45 minutes of bombs.”

By Nov. 2, 1999, “Still D.R.E.” was moving units as a single. Two weeks later, the album came out.

Dropping right in time to appear under Christmas trees, the leaf laden 2001 went on to sell almost 8 million units in the US alone.

Dre would return the favor for Flex’s invaluable co-sign by appearing on the Hot 97 DJ’s The Tunnel and 60 Minutes of Funk, Vol 4 projects.

Across the country, the 2001 momentum continued with the Eminem-assisted “Forgot About Dre,” with the originally intended first single, “The Next Episode,” rounding out the rollout of video releases and paving the way for that summer’s seminal Up in Smoke Tour.

From Chula Vista to Tampa Bay, the tour packed out arenas. Equally impressive, its corresponding DVD went 6x Platinum in the US and 8x Platinum in Australia.

Through “Still D.R.E.” and 2001, Dr. Dre was not only back — he was back on top.

The Legacy

In 2023, Dr. Dre may be more on top than he’s ever been.

With $200 million in his bank account from his catalog sale to UMG, $750 million from selling his stake in Beats by Dre, and over $200 million in Apple shares, Dr. Dre never has to work another day in his life.

Leaving behind Death Row Records and partnering with Jimmy Iovine made the music man financially set and secure in every sense.

However, it’s the success of his comeback classic that makes him cemented as a living legend.

“2001 was — and is still — one of the best albums,” multiplatinum Philly rapper Eve said of the LP. “It was an anticipated album within the industry as much as the public.”

The album led by “Still D.R.E.” lit the spark for peers and predecessors.

“For me, the bar for a compilation album is 2001,” Boi-1da told Boardroom in February. “Every single level was a master. That was a masterclass in raps, beats, production, mixing, everything. I listen to something off that album daily just to remind myself what I’m striving for. I listen to that album every single day to strive for that kind of greatness.”

Perhaps more importantly, it created the capital and momentum to dive deeper into the Interscope/Aftermath talent well — shortly after the release of 2001, Dre went on to produce back-to-back Diamond albums for Eminem.

Next, Dre directed the multi-Platinum debuts of Aftermath artists 50 Cent and The Game.

Years later, Aftermath inked Kendrick Lamar, an artist then managed by a Death Row alum. The sum of Aftermath’s powers was enough to have Dre and Snoop headline the 2022 Super Bowl Halftime Show: a first for hip-hop.

Perhaps to Jimmy Iovine’s dismay, they opened with “The Next Episode.”

Nevertheless, it’s “Still D.R.E.” that still sees streaming spins above a billion.

That lead single for 2001 set Aftermath on the path to becoming an industry power while also reintroducing the world to the genius of Dr. Dre in a broader sense. As a producer for hire, he won Grammy Awards with Eve and Gwen Stefani, making good on his ‘been there, done that,’ declarations about gangster rap back in 1996.

For anyone downplaying Dre, hip-hop, or his place as a musician, their arguments were now illegitimate from the perspective of peers, fans, and even the Recording Academy.

“What makes Dre different than any other producer is that he’s such a perfectionist,” Eve said. “He can hear things that I feel like normal ears can’t hear. There were definitely times that I was in the studio with him and he’d be like, ‘Say this word like this,’ and I’d be like, ‘What are you talking about?’ But as soon as you did it the way he asked, it would make a difference.”

Across eras, Dr. Dre’s excellence resonates.

“I say this all the time: Dr. Dre’s the greatest of all time,” Boi-1da said. “I strive to be as great as him one day.”

While 2001 was the follow-up to The Chronic that Death Row may have never wanted to happen, the world still awaits the long-rumored Detox. Like its Platinum predecessor, even if the project never sees the light of day, everyone from Jay-Z to Drake to Lil Wayne can say they’ve written on it.

But what’s immutable is that even nearly a quarter-century later, his 1999 masterpiece lasts the test of time even if the world expected it to be dead on arrival.

“Give yourself the time,” Iovine said in The Defiant Ones. “Whether it’s two months, three months, or a year, to make something that’s going to last forever.”

It does. Still.