Boardroom breaks down the roster construction wizardry that built the foundation for Heat Culture and won the South Florida franchise its first chip back in 2006.

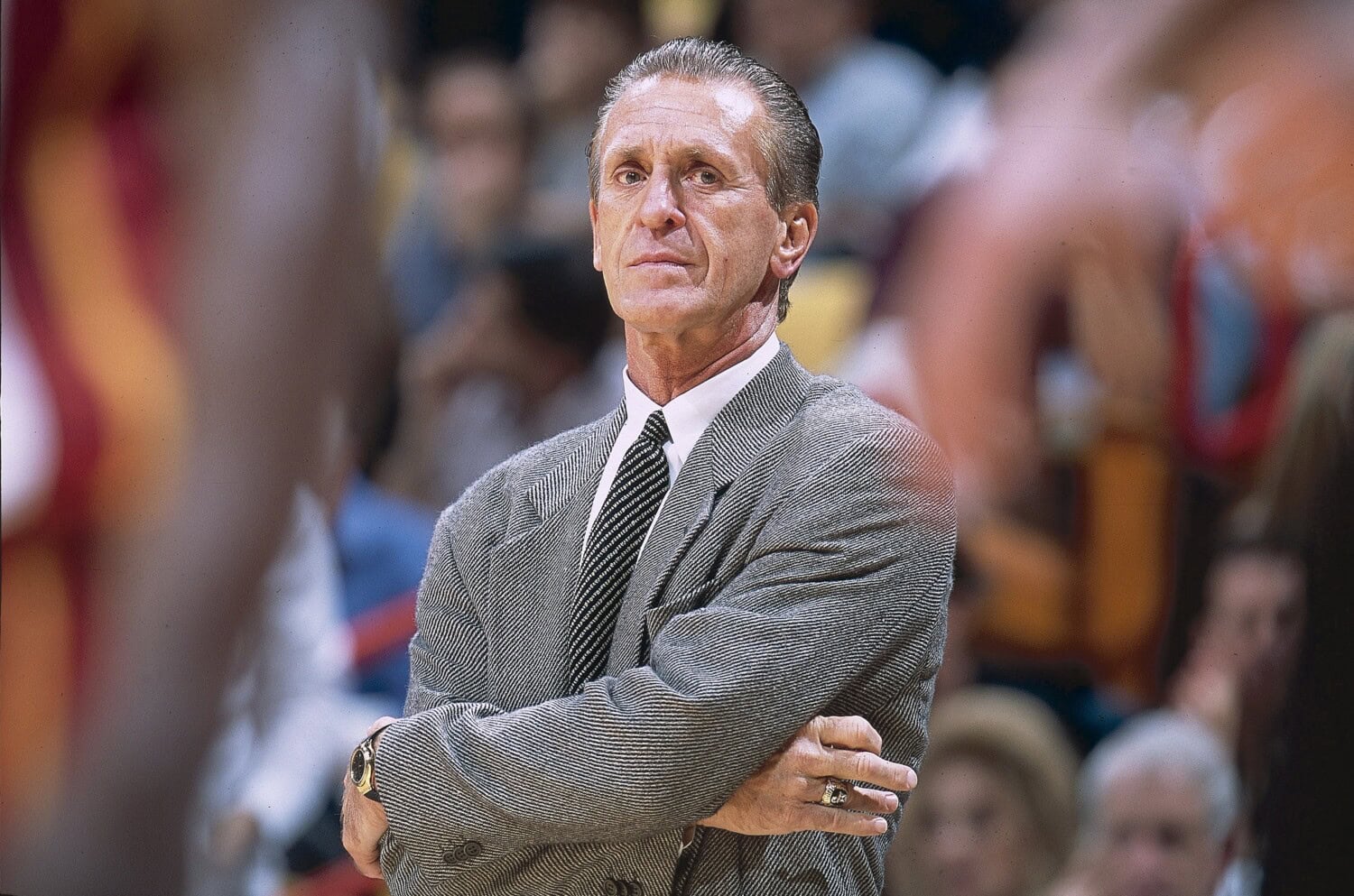

In 1995, Pat Riley faxed in a resignation letter to the front office of the New York Knicks.

The highest-paid coach in professional basketball was taking his talents to South Beach, joining up as both President and head coach of the Miami Heat. His new business partner was to be billionaire Micky Arison, the CEO of Carnival Corporation.

While the basketball lifer and the cruise line mogul both enjoyed good tans and lavish vacations, they possessed a shared focus on a different kind of ship: the kind that comes with a trophy and a ring.

Arison had purchased the Florida franchise just months before putting Riley in complete control of all things ball. Together the two would establish what came to be called Heat Culture: a wild worldview in which superstars become enthralled by the thrill of victory and the extreme disciple it takes to get there.

Florida provided a fertile home base where the lack of state income tax allowed for high-profile pay cuts. The Heat was an organization where role players and video assistants could rise to prominence. It was all there.

Appealing to the id of disgruntled talent, Riley and Arison have been able to lure the likes of Jimmy Butler, Alonzo Mourning, LeBron James, and Tim Hardaway to the magical market, craving competition and the company of those wired for the same.

It all happens on the beautiful backdrop of the beach, and it all started with a 7-foot-1 superstar.

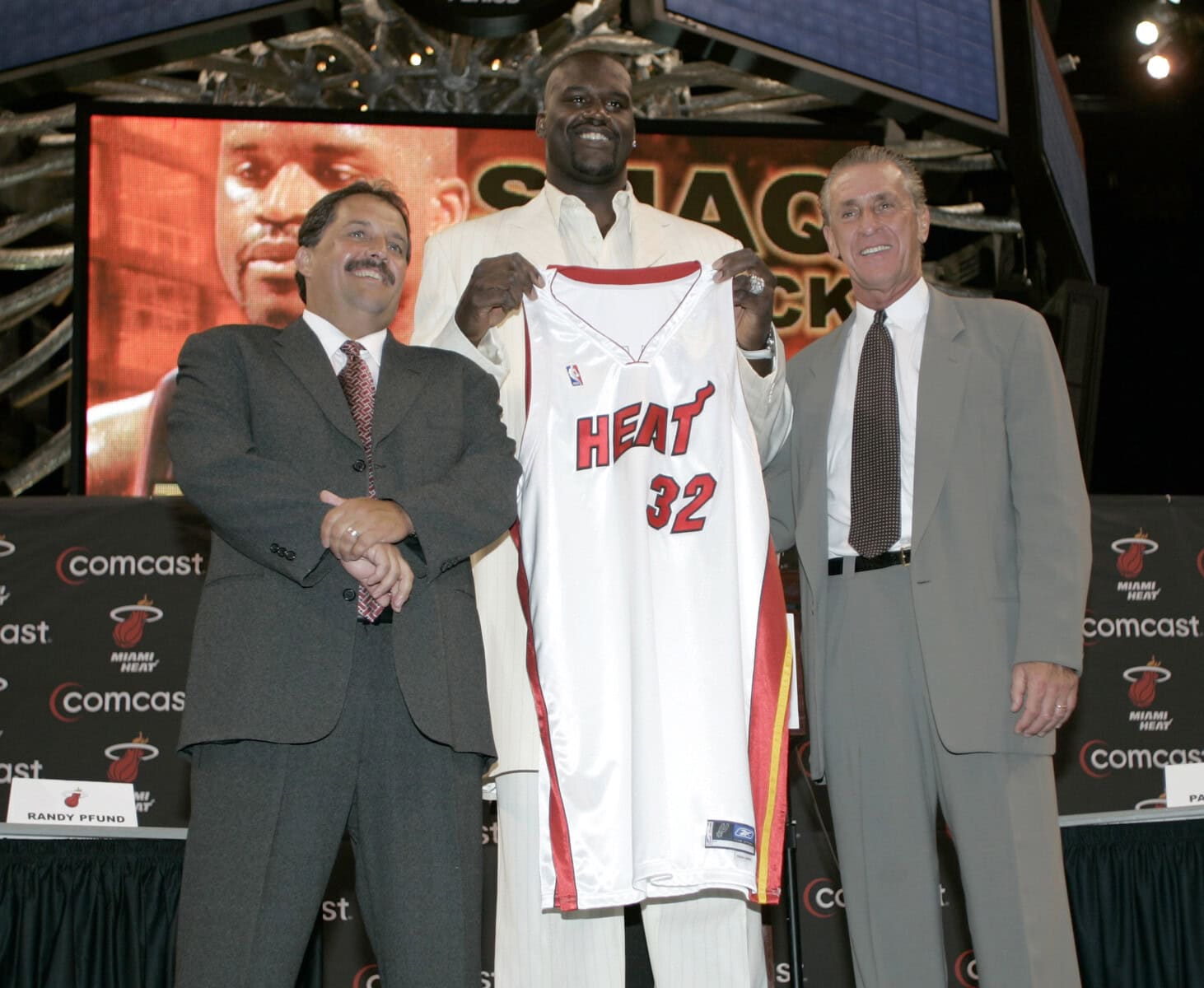

In the summer of 2004, Riley and Arison acquired Shaquille O’Neal, a $25 million-a-year active All-Star and former MVP hellbent on winning his fourth NBA title before his West Coast comrades.

Arriving in South Beach with super soakers and a vengeance, it was an unlikely partnership of two total opposites. Thankfully, O’Neal and Riley just so happened to share a convenient conviction: winning a championship at all costs.

Even to themselves.

Prioritizing rings over wealth and health, these two scorned Lakers pieced together an All-Star ensemble at a surprising level of affordability.

Boardroom breaks down the business behind two of basketball’s most powerful players who turned South Beach into Title Town.

Pat Riley, MD

Pat Riley is a Hall of Famer as an executive and a coach.

He’s also a doctor.

For over 40 years, Riles has made it his mission to cure The Disease of Me: the belief system that once teams start succeeding, individuals became more selfish. He’d seen it play out firsthand with the Showtime Lakers who won five rings in the ’80s but wrestled with pride and jealousy.

“Greed seduced the Lakers,” Riley wrote in his 1993 book, The Winner Within.

Oh, yes, Pat Riley is also an author.

Intended to be a business blueprint based on lessons from basketball, Riley’s writing foreshadowed his front office ascent.

More importantly, it revealed that despite his cutthroat competitiveness and Armani getups, his hunger for more was far from what Hollywood depicted in Wall Street. Gordon Gekko, the 1987 film’s character who looks like Riley and preaches self-interest, may appear akin to the high-paid coach in styling and success.

However, Michael Dougals’ too-real portrayal of the man’s nonexistent morals made Riley sick.

“A moment in the movie Wall Street crystalized for me the biggest reason why teams break down,” Riley wrote. “His clothing and his manner told you that he was successful, self-assured, in command… For much of the ’80s, greed defined the tone of the times. We’re just beginning to understand fully how much this greed orgy cost us all as a nation, as a team.”

Gekko claimed greed was good. Riley couldn’t disagree more.

Despite high status, styling, and success, Riley saw winning as a “we over me” imperative; to fully integrate his ethics he needed control for himself and buy-in from ownership to ball boy. In 1995, he moved to Miami with free rein over basketball operations, tasked with turning an expansion team into a contender.

For a stretch of eight seasons, Riley manned both the sideline and the front office, reaching the postseason six times but never winning a ring. In the summer of 2003, he handed the reins to assistant coach Stan Van Gundy. That same year, he selected a kid from Marquette named Dwyane Wade in the NBA Draft.

Riley may have been exhausted as a coach, but he was hungry as an executive.

A year after leaving the bench, he made good on his presidential power by trading for three-time champion Shaquille O’Neal. The superstar center arrived in an 18-wheeler, handing over his ego and passing the keys to Riley — and a rookie.

Diesel Power

Shaq started many a season in Los Angeles recovering from strategically scheduled surgeries.

He began his first year in Miami in the best shape of his life, aligning business interests on and off the court.

“I just bought a house on the beach and my wife likes me to walk naked on the beach,” Shaq said at his introductory press conference in 2004. “My good friend Mark Mastrov, CEO and President of 24 Hour Fitness, is here. We’re bringing 24 Hour Fitness to Miami. We want you all to get in shape and look as good as me.”

Investing in his health literally and figuratively, the Big Aristotle set out to reclaim the narrative of his legacy as a player.

“Orlando was fun, LA was business, Miami was redemption,” Shaq told Kevin Garnett.

The first step for the most dominant big man of all time was getting in shape. The second was relinquishing power. However, it was not Riley he was handing control over, but rather, a 22-year-old Golden Eagle who had hardly been recruited as a Chicago high schooler.

“I saw something in D Wade,” Shaq told the Knuckleheads podcast in 2020. “I saw a mixture of Penny and Kobe.”

Wade would not only get the ball; he’d get the team.

“You the man, you’re the CEO, I’m the consultant,” Shaq said on Stephen Jackson and Matt Barnes’ All the Smoke in 2021.

Only in his second season in 2004-05, Wade would be CEO while working on a starting salary.

At $2.8 million a year, he was making almost $25 million less than Shaq Diesel, yet he was still empowered to be in charge. The tandem flourished upon pairing, each making the All-Star Game and taking the Heat all the way to the 2005 Eastern Conference Finals.

Despite gaining a 3-2 lead in the series, the man who arrived in an 18-wheeler would be ousted at the hands of the Detroit Pistons.

Hell-bent on building a winner, Shaq spent the offseason not under the knife, but cutting his contract. Just the same, Riley postponed a hip replacement in favor of roster reconstruction.

What took place was the most surgical summer the NBA had ever seen.

15 Strong

On Aug. 2, 2005, Shaquille O’Neal signed a 5-year, $100 million deal with the Miami Heat.

While making $20 million a season is nothing to sneer at, it was a dramatic pay cut given he opted out of his existing contract set to pay him $30.6 million that same season.

“Shaquille can name his price,” Perry Rogers, Shaq’s agent at the time, told ESPN. “And the price he named was winning.”

“It’s never about money,” Shaq said when first arriving in Miami. “I invested in Google a long time ago.”

Though the big man’s commitment was secured, Riley had an additional pact in place: Not just to acquire winners, but the ones Shaq wanted.

Hours after O’Neal signed, Riley orchestrated the biggest trade in NBA history.

Making maneuvers with five franchises, Riley acquired Antoine Walker, Jason Williams, and James Posey all on the same day.

“Outside of Steve Nash and Jason Kidd, there isn’t a better open-floor, half-court playmaker in the league than Jason Williams,” Riley said at the time of the trade. “Antoine is one of the very best multi-faceted, versatile players in this game. Posey is going to be the perfect complement to Shaq, Dwyane, Walker, Williams, Udonis [Haslem], etc. because he is a defense-oriented, slashing player who can run the break, play above the rim, and will make the open three.”

Stylistically, Riley and Shaq had guys who wanted to win. True to Shaq and Miami, it was all about dominance and fun.

Instantaneously, the synergy was felt on and off the court.

“I never partied and played basketball like that in my life,” Walker told Boardroom in 2022. “We made sure we had a good time. We kicked it as well as played ball at a very, very high level. That was one of the most fun seasons I’ve ever been a part of.”

Weeks after acquiring Walker, Williams, and Posey, the Heat doubled down at point guard by picking up future Hall of Famer Gary Payton.

Although the nine-time NBA All-Star had made $5.4 million the previous season on a struggling Celtics squad, he likewise took a pay cut to play with his friends — and win a championship ring that had eluded him for 15 years.

“Anybody who comes into Miami? If they sign on the dotted line, then they’ll understand what we’re trying to do here,” Wade told the Associated Press in 2005. “He knows we’re about winning right now.”

Taking the veteran minimum of $1.1 million per year to come off the bench for the first time in his career, it was Riley’s winning pedigree and Shaq’s sales pitch that sealed the deal.

“I wasn’t supposed to play a lot. I only came because of Shaq,” Payton told TNT in 2017. “I was the oldest guy on the team, but he was our rock. We all went out all the time; we just had fun. We were one of those groups that were together, and on the court, it made us better.”

After all, the Glove wasn’t the only accomplished All-Star to take less money and a diminished role.

Midway into the previous season, the Heat brought back beloved center Alonzo Mourning, who was a cornerstone in Riley’s first years with the team but had been more recently on the mend recovering from a kidney illness.

Like Gary, Zo signed for $1.1 million to chase a title in South Beach.

“This is not about sentiment; this is about winning,” Riley told the AP in 2005. “We want to win and it’s all about business, and it’s about business with Zo. We have an opportunity to get a big man, and if it wasn’t Alonzo, we’d be searching out there to get another big man.”

Walking the same walk, Riley himself had taken a pay cut only two years prior in his role as President to prevent the need for layoffs across the franchise.

Heading into training camp, the Surgical Summer was complete.

Following Shaquille O’Neal’s example, a slew of veterans accepted reduced paychecks in the name of winning. The Disease of Me had been extinguished in the house of the Heat before the embers became flames. Teammates were hanging out together and All-Stars were coming off the bench.

Soon, it would be President Riley himself that would be on that same bench.

“The day you decided to take over, I knew we were going to win,” Shaq said of Riley at his jersey retirement in 2016.

Win at All Costs

The summer of 2005 was a formative one for the Miami Heat.

The fall was, too.

Having handed coaching duties over to Stan Van Gundy just two years prior, Pat Riley decided the only man fit to coach this team was himself. 21 games into the season, Van Gundy resigned. Riley returned to the bench.

“I have an obligation to this franchise,” he said in Dec. 2005. “I’m going to put off my hip replacement surgery. I have a responsibility to this team, to the players I traded for and signed. Right now, at this moment, I’m the best person to do that. As far as the other things that go into the game, I can handle that.”

Instantly, his presence was felt.

“Playing for the great Pat Riley? Being able to play for a guy of his stature was special,” Walker said of the big decision.

Reinvigorated, the Heat turned around a slow start marred by injuries and the coaching question to finish the regular season 52-30 and No. 2 in the East.

Though Shaq attests the team should’ve gone 79-3 given the wealth of talent they had, it was Pat’s presence in the boardroom and the locker room that turned the team into a true contender.

“He’s probably one of the greatest motivators,” Shaq once told TNT’s Ernie Johnson. “His speeches and his stories, I always tell people that’s what took me to the next level. Not training, not being in the gym three hours; [it was] conversations.”

Those conversations with Riley lit a fire in Shaq. However, talk is cheap if you don’t win, and each player on the team was taking it on payday considering their estimated market value.

That season, the Miami Heat payroll was $60.7 million, coming in at just 15th overall in the NBA.

The difference in take-home income compared to the rest of the league’s upper tier couldn’t have been more apparent when Riley and Shaq’s squad finally reached the promised land of the NBA Finals.

Across the court, the Mark Cuban-owned Dallas Mavericks had the second-highest payroll in the entire NBA, coming in at a whopping $98.4 million. That summer, they had even waived two-time All-Star Michael Finley as a means to avoid the league’s new luxury tax.

Still, he was the team’s highest-paid player on the books $15.9 million despite playing said season with the San Antonio Spurs.

Down the line, the Mavericks had an expensive but balanced payroll ranging from Keith Van Horn and Dirk Nowitzki making just north of $13 million that year to role players like Jerry Stackhouse in the $8 million range and Devin Harris cashing just below $3 million.

The value signee that made it all go, however, was Josh Howard: a late first-round pick in 2003 out of Wake Forest who was on the third year of his rookie contract.

Because of this, Howard was making only $923,880 — almost $8 million less than veteran big man Erick Dampier — despite being third on the team in scoring and total starts.

In the NBA Finals, it all amounted to an early 2-0 series lead in favor of the Mavericks.

If Pat Riley had to convince his whole roster a year ago to take pay cuts, he had to prove his buy-in as well.

“He came in with a bucket full of ice,” Shaq recalled in 2020. “He said, ‘Do you guys believe I can hold my head in this bucket of ice for three minutes?’ Most of the guys were like, ‘I don’t believe he can do it.’ And he did it. He almost died, but he did it. So the first thing you have to do is believe.”

The belief started after that ice bucket.

Given all that was to follow, it’s more than fair to say that it hasn’t stopped since.

Fire & Ice

Following Riley’s subzero submersion, the Miami Heat went on to win the next four games in a row, giving Pat his first title in South Beach and proving Shaq strong on his word.

Dwyane Wade won Finals MVP in a performance for the ages, far exceeding expectations of a rookie contract that still paid him $3 million a year.

When it was all said and done for Flash, he’d win three titles in Miami, earn his spot as one of the greatest shooting guards of all time, and make nearly $200 million in on-court salary alone.

He helped establish Heat Culture for the 2006 championship team in a way that belied his 24 years of age. Years later, the same sense of leadership and opportunity exemplified by Riley and Shaq inspired Wade when he took a pay cut himself in 2010 so the team could sign LeBron James and Chris Bosh, making a run at glory all over again.

For those stationed in South Beach for the tide-changing 2005-06 run, the team-first approach still serves as a memory and model for we over me.

The innate balance of discipline and fun — while sacrificing either cash or playing time — was a cornerstone of the kind of winning atmosphere only equal and opposite personalities like O’Neal and Riley could cultivate.

“Miami was special because it was the first time I had gone into a season where the expectation was to win an NBA title,” Walker said looking back. “That was the goal — anything less than that was a disappointment. It created a different culture and approach to the game which I enjoyed. We were all so close. It was the first team I ever played on where it was hard to not catch six or seven guys out to eat on the road. You seldom see that in the league, guys hanging the way they hang.”

This summer, despite regular season struggles that threatened to leave them on the outside looking in, Miami found itself back in the playoffs with different expectations, but the same well-honed structure.

This time, their bargain bin bench is not full of All-Stars or late-career future Hall of Famers searching for a ring, but rather overlooked talents like Caleb Martin, Gabe Vincent, and Max Strus not so far removed from fighting for a spot in the league. Nevertheless, this year’s team has reached a similar status in the Finals despite drastically different supposed ceilings.

Enduringly, the Heat Culture cachet and optionality of the team’s pending payroll heading into the new collective bargaining agreement gives Riley and the Miami franchise a real shot at thriving for years to come despite the introduction of a second luxury tax apron meant to impose new roster limitations on the league’s biggest-spending teams.

Perhaps it’s a frugal approach to free agency and a maniac manner in which physical conditioning is king. Maybe it’s Riley’s proactive attitude towards curing The Disease of Me before it even has a chance to metastasize.

In any event, Heat Culture has cultivated a next-man-up mentality that democratizes depth and quite simply begets winning.

In the summer of 2005 to the summer of 2023 and every summer after, a focus on rings remains the pinnacle to Riley, whether on the bench or in the front office. It came to fruition first with Shaq, who’s still basking in the pride of his final championship ring (and his Google stock dividends) to this day.

Stalwarts such as Alonzo Mourning and Udonis Haslem remain active in the organization — the latter is still technically an active player at age 42 — instilling the same principles that brought Miami its first title in 2006. It’s a culture fostered over time that’s guiding today’s talent, but never lost on those that were there for the first Finals that started it all.

“No matter if we fought, the common goal was to win an NBA Title,” Antoine Walker said. “And we were able to accomplish that.”