Learn how the spendy summer smash blazed open new lanes for Jermaine Dupri and Jay-Z .

Last weekend, Formula 1 took place in Miami while Louisville hosted the Kentucky Derby.

Twenty-five years ago, they both went down in Atlanta.

Dressed in all yellow while showing no signs of slowing down, Jermaine Dupri and Jay-Z switched lanes and took turns rhyming on 1998’s summer anthem, “Money Ain’t a Thang.”

Although neither artist was new to flossing, the merging markets they were approaching had never seen or heard something so authentically aspirational and glossy before. For both Jay and Jermaine, they found themselves trying something new and winning handsomely.

From racing horses with Real Housewives to taunting Baywatch babes with bags of Benjamins, the ballers in baseball jerseys proved stunting was not a habit but rather a sport. America’s Game, capitalism, belonged to the two titans and rap radio would never be the same.

Simply put? If you could spend with the best of them down South and keep pace with rap royalty from up North, you had a hit record that defied demographics.

A quarter century since its release, Boardroom breaks down the massive spark “Money Ain’t a Thang” provided for Hova’s road to No. 1 and JD’s path from R&B scribe to rap’s reigning ringleader.

Welcome to Atlanta

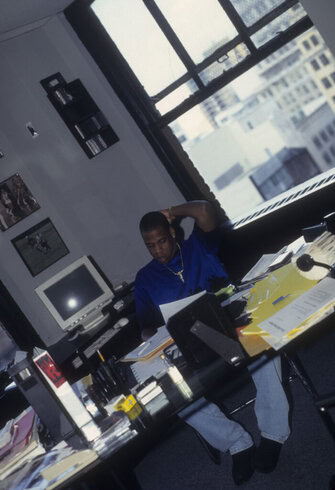

Jermaine Dupri was only 25-years-old when “Money Ain’t a Thang” blew up.

Make no mistake, JD was not new money.

Raised in the record industry, Dupri moved from North Carolina to Georgia when he was barely old enough to walk. At an early age, he observed his own father, Michael Mauldin, climb the ladder from touring with Cameo to being President of Black Music at Columbia Records.

“My dad was basically a roadie that turned into a road manager that turned into a production manager,” Dupri told the Questlove Supreme podcast. “My dad played drums and then he morphed into doing production for all of these artists. I used to be in rehearsal watching.”

Observant since elementary, Jermaine was popping by the time he was a teenager. Whether on stage in Atlanta or on the road with his pops, young Jermaine was starring in breakdance competitions and learning how to scratch from Jam Master Jay.

Similar to his father, he could spot talent because he was talent.

The deejay/dancer quickly transitioned into manager/songwriter, penning his first No. 1 record — Kriss Kross’s “Jump” — at only 18 years of age.

From 1992 to 1996, the Atlanta prodigy was running radio in an R&B sense.

While production placement on Ma$e albums and launching Da Brat came with commercial clout in the rap game, it was writing songs like Mariah Carey’s “Always Be My Baby” and CrazySexyCool cuts for TLC that placed Dupri in a whole different tax bracket.

From child star to all-star, JD decided what was now and who was next. His whole life, he’d embraced the new and existed as both.

Soon after Kriss Kross, he was launching the career of Usher while throwing parties in Atlanta that the likes of Suge Knight and Elton John flew in to attend. Having started So So Def with his father at only 19, JD had the city on lock.

Not only did he know what a hit song sounded like, he knew what it looked like.

Through hits from Mariah and My Way‘s 7-time platinum success, the industry at large was well aware of the 20-something super producer.

Lucky for Dupri, an early listener happened to hail from Marcy Projects: a place where they ball and breed rhyme stars.

Funny enough, it’d be a Sisqo song that changed the course of each artist’s career.

Streets is Listening

Jay-Z was not a rapper, he was a hustler that just happened to rap well.

Unlike Dupri, Shawn Carter did not grow up with wealth or a well-connected father.

Forging his own road map, multitasked his time on the corner with writing and remembering rhymes in his head. Rap was never the plan as other ambitions loomed closer to home.

“I’m from Bedstuy,” Jay told MTV News in 1998. “I didn’t live next to doctors or lawyers. I lived next to hustlers and that’s the people that I grew up looking up to. That’s the things that were most attainable to me. I got to see the cars. It’s material, but it’s the things that I grew up seeing.”

Parallel to Dupri, Hov had big dreams even if he didn’t have a resident role model to show him how to get there.

In the late ’80s and early ’90s, Jay’s acumen as a rapper led to looks from Jaz-O, Big Daddy Kane, and Big L. Without funding from his father, he teamed up with Dame Dash and “Biggs” Burke to launch Roc-a-Fella Records in 1995.

While Dupri was running R&B radio and turning teen talents into Tiger Beat cover stars, Jay-Z was writing records never intended or expected to get picked up on MTV rotation.

His debut album, Reasonable Doubt, was critically acclaimed but commercially slept on.

Though the first Roc-a-Fella release benefitted from Mary J. Blige and Notorious B.I.G. features, most songs were too slow, smart, or violent for radio.

The only exception was “Ain’t No…”: a surprise single that saw Hov write a verse for a 17-year-old known as Foxy Brown.

Though the buzz behind the song wasn’t enough to push Reasonable Doubt to mass market success, its placement on The Nutty Professor soundtrack moved mountains.

With one cinematic placement, fans heard Hov in movie theatres around the country thanks to a film that grossed $274 million at box office.

By brokering a deal with Russell Simmons to get “Ain’t No…” on the Def Jam distributed Platinum soundtrack, Jay was now in regular rotation on music video countdown shows even if he was an independent and relatively underground artist.

“We learned about the business through that record,” Jay told MTV News. “We had a little of bargaining power. Our lack of knowledge of the business was made up because we had a hit record. A hit record helps you out, it makes you smarter than you really are.”

Rather than retire off one album, Jay went back to bat with 1997’s In My Lifetime, Vol. 1.

Aiming towards the commercial cache of “Ain’t No…” while attempting to appease core fans, critics considered his sophomore smash a sophomore slump, suggesting that Jay missed both marks even if he went Platinum in a week.

To have sustained success, Hov had to leverage his street sensibility with production bouncy enough to dance to.

Rather than rely on the production of Harlem like Puff Daddy and the Hitmen or local lacers like Trackmasters, Jay opened his ear to the South.

Industry Infidelity

By 1997, bi-coastal conflict had taken two of hip-hop’s most talented superstars.

Because of this, recording across enemy lines lived as a no-no.

Despite 2Pac producing some of his most spirited work with the Live Squad in Queens or Biggie having love for California, the tension in the air from the murders of both made recording in other regions a risk most wouldn’t take.

Even when Nas and Dr. Dre crossed coasts to form The Firm, the album flopped with fans and artists alike assuming the genre would only become more insular.

Adjacent to all the rivalry was Jay-Z. Having lost his Commission collaborator in B.I.G. and perhaps lost his fans with Vol. 1, he leaned into pain and partying when working on his highly pivotal third album.

When it came to the partying part, no one was better than Jermaine Dupri.

Working with Dru Hill, an R&B outfit from Baltimore fronted by a singer named Sisqo, Dupri placed himself and Da Brat on the aptly branded “Sleepin’ In My Bed (So So Def)” Remix.

The genius of the reworking was not just joining DMV, Atlanta, and Chicago listeners on one record, it was flipping a ballad about being cheated on — in one’s own home, no less — into an upbeat dance record.

In an instant, Jermaine Dupri’s sound, style, and solo presence were making the rounds on radio and television across the country.

This audience included New York and it included Jay-Z.

Just as Hov had an ear towards what was working commercially across the industry, Dupri kept an eye on what was bubbling beneath the surface on the mixtape circuit.

Fluent in the position DJ Clue played in New York City’s sizzling freestyle circuit, he heard Hov ad-libbing the same sentences he had just dropped on the Dru Hill record.

Keep in mind, this jacking for beats all took place at a tense time despite Dupri’s dancing. In that era, many blamed the media for the East Coast vs. West Coast rap rivalry and the lives it took. Looking to change the narrative, magazine XXL took it upon themselves the same year Biggie was slain to increase the peace.

In doing so, they commissioned a cover shoot in which rappers and industry members from all over would congregate in Harlem to recreate an Esquire jazz shoot done in the same space in the ’50s.

That’s where Dupri and Jay-Z would first become friends even if hours earlier they learned they were each fans.

“That day that I got to New York, I heard a Clue mixtape,” Dupri told DJ Vlad in 2018. “Jay took a part from a Dru Hill remix I did but he changed the lyrics. Me being from Atlanta? I didn’t think rappers from New York were paying attention to what I was doing at that level, especially a rapper like Jay-Z.”

Despite hailing from vastly different backgrounds, Hov had the rap credibility Dupri desired while JD captured the commercial appeal Jay needed to grow.

Exchanging info, Jay quickly booked a flight to Atlanta soon finding that despite their differences they dreamed, worked, and celebrated just the same.

Under Pressure

There are two types of fans that liked Jay-Z’s second album.

Those that like “Imaginary Player” and those that like “Sunshine.”

Though Hov was enjoying the sales success of Vol. 1, he was working diligently at its successor, aiming to appease what he saw as a booming audience while still playing his part as both boss and baller.

“I don’t do too much besides party,” Jay told MTV News. “When I’m not recording, I’m in the office. When I’m not in the office, I’m recording.”

Not living under a rock, Jay-Z knew the market for crossover singles was massive even if backpackers were looking to beat down anyone who dare dabbled in jiggy music videos or pop sounds.

In growing the genre at the mainstream touch points you could grow exposure for all MCs who operated underneath.

“When you have artists such as Puff or Will Smith that have big commercial success? People look a little deeper and want to find out what’s happening over there,” Jay continued to MTV News. “Artists with commercial success are bringing the whole gamut of people over.”

Not just new people, new hemispheres.

“Rappers don’t usually get to go out and tour the whole globe,” Jay told MTV in 1997. “They usually get club dates, colleges, things of that nature. But you perform in front of 15,000? That’s rare in rap. That man Puff opened a lot of doors for rappers. If this whole thing goes right, hopefully we can go on tour every year like The Rolling Stones and Green Day.”

While in the air from the Big Apple to the Peach State, Jermaine Dupri was operating on the same wavelength Jay was riding on but from an opposite approach. They had a clear connection even if they came from different paths.

“From that day forth I felt this energy between me and him,” Dupri told Vlad. “We saw and thought a lot alike. He came to Atlanta and on the way to the airport I started thinking about what I wanted the hook to be.”

Hov’s new friend was playing the MC’s old work in his car, running back “Can’t Knock the Hustle” when a line hit him:

I’m deep in the south kicking up top game

Bouncing on the highway switching four lanes

Screaming through the sunroof, ‘money ain’t a thang!’

“He’s talking about Atlanta,” Dupri said. “That’s what I’m visualizing.”

While Jay was waxing poetic in black and white, JD was ready to take his storytelling to technicolor.

Having just looped up Steve Arrington’s “Weak at the Knees,” Dupri picked up Jay, and the two artists hit the studio.

Running back the beat a few times, Jay told Dupri he was ready to hit the booth despite only nodding for a few minutes and not jotting a single line down.

The super producer and scribe for Mariah Carey was not only impressed, but he was also forever changed.

“That was the last day I wrote on paper,” Dupri says. “I haven’t written anything since then.”

Off to the Races

As legend suggests, “Money Ain’t a Thang” only took a sole session to write and record.

From there, it was set up to serve as the bridge between Jay-Z’s second and third albums as well as the second single for Dupri’s debut solo album. As it often goes, the labels had other ideas.

“At this time, Columbia was paying attention to the success of Jermaine Dupri,” JD told HipHopDX in 2019.

Signed as a solo artist to a place where his proud pops worked, every industry head in the meeting pushed Dupri to release “Sweetheart” with Mariah Carey as the album’s second single. The formula was safe and likely lucrative.

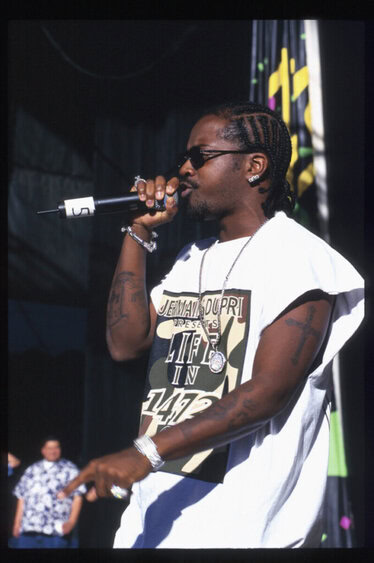

Rather than double-down on R&B radio’s built in buyers, Dupri sought a real hip-hop audience to embrace his entrance into rap solo stardom, Life in 1472.

“I wanted people to respect it for being a real rap album,” Dupri said. “Setting the tone with ‘Money Ain’t a Thang’ was very important for me.”

Having already toured with Biggie when on the road with Da Brat, Dupri understood the iron fist with which NY ran the rap world while also understanding Atlanta’s ability to resonate with different rooms.

Casting himself and Hov as cultural equivalents to Robin Leach and Ralph Lauren, the two fast friends made a movie in the very literal since. In the high-budget visual, they went from daydreaming poolside to racing cars and horses with Traci Bingham and Kenya Moore.

“We actually wrecked a Porsche on that video shoot,” Dupri says.

With Don Chi Chi and Iceberg Slim speeding in Ferraris, dancing like Will Smith, and comparing bracelet prices, they made a movie dripping in luxury lifestyle that all walks of life could cheer for and aspire to.

Hov’s clever quotables were now being recited in suburban schools while JD’s beats blazed through car stereos in Manhattan.

It wasn’t pop pandering, it was simply returning to the dream world rap reveled in a decade prior.

“Slick Rick is my favorite rapper of all time,” Dupri told Drink Champs in 2017. “That’s my idol.”

In short order, “Money Ain’t a Thang” became a mainstay on MTV and BET.

It sent Dupri’s solo debut to No. 1 on the US R&B Top Album charts, eventually going Platinum in America. This was all despite Columbia not putting the full-court press on radio to work the single.

“That’s my biggest non-No. 1 record,” Dupri said. “I finally made a record that’s credible and the culture loves. The chart success might not have been there, but right here? It’s cemented.”

With one song, Jermaine Dupri was validated by an entire coast.

Quickly, his co-star was set to take over the entire world.

Third Time’s the Charm

When “Money Ain’t a Thang” released at radio on May 11, 1998, Jay-Z was between albums but not beside himself.

Sensing the moment, he released Roc-a-Fella’s first film, Streets is Watching, straight to VHS as a gritty contrast to his glossy guest spot.

As “Money Ain’t a Thang” gained momentum on Dupri’s album and through The Source Presents: Hip Hop Hits, Vol. 2, Jay had mass market exposure while still holding a firm foot in Marcy.

Later that August, he released “Can I Get A…” as the lead look for Vol. 2…Hard Knock Life, introducing the world to Ja Rule and Amil while appearing on the wildly successful Rush Hour Soundtrack.

Learning lessons from Def Jam’s theatric placement of “Ain’t No…” and the erratic aims of Vol. 1, Hov was in pole position to attack all lanes at once with the same prowess as Puff but with more credibility than Will Smith.

“It was one of those times when I got into a groove. Right now, we have two songs that are so crazy,” Jay told MTV News in ’98.

“Vol. 1 we took it from being in the street to being in the music business and dealing with that pressure,” Jay said. “Now I’m staying a little longer and am more in control of everything – not just rapping and music but the whole overall project.”

When Vol. 2…Hard Knock Life released on Sep. 29, 1998, Jay-Z was en route to being the biggest artist in the world. As he wisely predicted, it was a case of a rising tide lifting all ships as hip-hop itself was dominating the charts.

Hov had his first No. 1 album and his peers weren’t far behind.

“In the Top 10, everybody is holding their position down stronger than it’s ever been,” Jay told Oneworld in 1998. “For the hip-hop purists who look down on that? All it’s doing is bringing the media to look at hip-hop. The more educated the consumer becomes the more they’re going to know that this is the pure, this is what I want.”

In that moment, Jay-Z, Outkast, and Lauryn Hill were all on fire commercially while still keeping their chops culturally.

Setting the spark with “Money Ain’t a Thang,” Jay-Z and Jermaine Dupri showed a mass-market audience what fun looked and felt like. It was aspirational without being demeaning. Easy to recite without being dumbed down.

To sell a dream you had to live that dream, with the coastal collaboration introducing Jay-Z’s uncanny cool to JD’s unmatched ability to start a party. Finally, Hov was able to cash in on his tastemaking equity.

Just the same, Dupri was set up to do what he sought after: run rap and amplify Atlanta.

With one song which spanned two albums, JD became established as a hip-hop heavyweight while Hov finally cracked the code on being bigger without selling out.

The same sensibilities led to spiritual successors like “Big Pimpin'” and the “Welcome to Atlanta” remixes — roundhouse records that once again mixed regions and impacted both culture and the charts.

Despite rap’s great divide, JD and Jay-Z found a way to smarten the market up simply by lightening it up. To this day, “Money Ain’t a Thang” still holds up at a party in any city or while switching lanes in any car.

Most of us don’t live like Jay-Z or Jermaine Dupri. But that track — and the corresponding visuals — made us realize, wouldn’t we all like to?