Nike’s Phil Knight wanted a rebel. Spencer Haywood wanted equity. The only problem? An agent wanted cash.

Imagine a big man who could give you 30 points and 20 boards a night.

For a whole season.

As a rookie.

At 19.

That man was Spencer Haywood.

By the early 1970s, the basketball superstar was well on his way. Already adorned in high-honor hardware from the Olympics, ABA, and NBA, Haywood had every accolade a hooper could ever dream of before he was old enough to rent a car.

And off the court, he was every part the icon, defeating the National Basketball Association in a revolutionary lawsuit that went all the way to the highest court in the land.

“The Supreme Court said that you couldn’t stop a person from making a living in America,” Haywood recalled to Boardroom. “Even though you could send them off to war at age 18. ”

Yes, at the tender age of 21, Haywood challenged the NBA’s age limit and thus young talent’s right to reach their earning potential. In doing so, he paved the way for future greats like Michael Jordan, Kobe Bryant, LeBron James, and Kevin Durant to turn pro before finishing four years of college.

Spencer Haywood was a hooper, a trailblazer, a rebel.

Spencer and the Swoosh

His All-Star stature and defiant spirit spoke to GMs eager to fill seats, kids looking for a hero, and supermodels searching for a husband.

Most of all, it spoke to Phil Knight.

Early in his ascent, the bossman at the newly named Nike had found the athlete born to push his products. After years of navigating the racing and jogging categories, Knight was ready to take over all athletic endeavors by branding the best and brashest with Swoosh-marked sneakers.

“There was a lot of media around me, so Phil wanted me to rep the shoe,” Haywood said. “I didn’t have any impression of Nike at that time because I had just gotten out of the Supreme Court case and was excited to play basketball.”

Haywood was the perfect fit for the brand’s introduction to basketball. Long before Knight would outfit MVP talent like Michael Jordan or defiant programs like the Georgetown Hoyas, Haywood had the it-factor as an athlete who stood for much more than just scoring, carrying himself with a contagious swagger.

Even better: Haywood played for the Seattle Supersonics, a franchise in driving distance of Knight’s Oregon home.

Still, Nike was in its infancy at that time, unproven on the hardwood and ultimately new to the world at large. Most top-level talent at that time was taking checks from Adidas and Converse, rarely risking tried-and-true product for the chance at building something with a new brand.

“The first time I wore the Nike Blazer was as a prototype in LA in the 1972 Olympic Games before they brought it to market,” Haywood said. “Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry West, and Oscar Robertson were all on the team. Wilt said, ‘What are you doing with this shoe? That ain’t nothing but an upside-down Newport!’”

Despite jokes from his All-NBA peers, Haywood liked Knight and felt it right to take a chance on Nike. After all, both were making their livings in the Pacific Northwest, a region where both ballplayers and brands could be overlooked due to big-city bias.

Signed, Sealed, and… Sold

After playing in sample product and discussing terms, the table was set: Nike would sign the hardwood hero who just battled the NBA in the Supreme Court. For Spencer Haywood’s talents, courage and endorsement, he would be granted equity in the company that was trying to come up.

Reports vary on just how much equity Haywood was to have in Nike. Knight, not known to give out equity easily in the Blue Ribbon Sports days, even to his closest comrades and most crucial financiers, was taking a big risk. However, by signing Haywood, he would have eyeballs attached to his product in his beloved Pacific Northwest.

The endorsement formula had already worked in track with Steve Prefontaine. How big could it become in basketball?

Signed, sealed, delivered, Knight had the face of his basketball brand and Haywood had his equity.

The only problem? Haywood’s agent insisted on his cut of the deal. And there would be no stopping him.

“I went on the road and he had the power of attorney letter,” Haywood said of his agent. “He couldn’t figure out how to get his 10%, so he sold my stock for the cash.”

Haywood was devastated. Not only had his agent stolen future earnings of life-changing proportions, but he had advised him to take the equity in the first place.

“My agent was preaching to me at the time to not take the money for tax advantage purposes,” Haywood said on the initial Nike contract. “We agreed on that, but he got greedy. He couldn’t figure out how to get that percentage instead of asking me for $10,000 out of $100,000 and moving on.”

At the time, Haywood’s agent selling his stock amounted to what’s now considered peanuts. Over time, the value of the stock has since amounted to much more.

“I lost about $2.8 billion,” Haywood said.

Yes, had Haywood been able to hold onto his stock options from his original Nike deal, he’d be a billionaire.

Sadly, in that era, agents robbing an athlete of color of his riches was considered a badge of honor by the most rotten among us. Haywood was not the only All-Star who was taken to the cleaners by a crooked agent, but by several orders of magnitude, he’s the one who suffered the most economically.

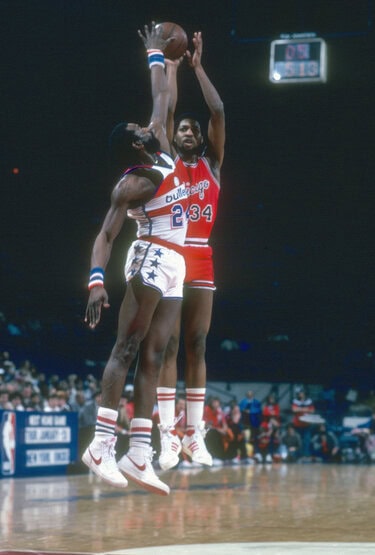

But over the course of his playing career, Haywood remained loyal to Nike despite the damage that had been done. First endorsing the Swoosh in Seattle and later landing in Los Angeles, New York, and DC, Haywood kept Nike Blazers and Nike Bruins on his feet.

“I was still with Nike until the time I retired,” he said.

Good Karma and Good Business

Exiting the NBA as a player in 1983, Haywood had endorsed Nike for a decade and laid the blueprint for the brand to secure the best talent in basketball for generations to follow. Between fighting the biggest institutions in basketball in the courtroom and helping to build sportswear’s biggest brand on the court, benefactors of Haywood’s courage in the 1970s are becoming millionaires and even billionaires today.

For Haywood, it’s not just good karma. It’s good business for the athletes, the brands, and the NBA.

“One of the greatest business deals I’ve ever done is deciding to fight the NCAA, the NBA, the ABA, and their four-year rule,” Haywood said. “By knocking that out in 1971, I’ve created $32 billion in player salary.”

In his post-playing days, Haywood has become an ally to the game and a conduit of change. He’s the subject of a book and a documentary, as well as an advocate for players’ physical and mental health care. Following his agent’s wrongdoings, Haywood started studying business and invested in real estate from Salt Lake City to his high school hometown of Detroit.

All told, despite the sour start to his Nike deal, he remains friends with Knight to this day and attends the Pac-12 Tournament each year with him.

“That’s my guy,” Haywood said of the founder. “I’m so proud of what he has done with Nike because I knew it when it was just one shoe. It was the Blazer and that was it. That was the only basketball shoe we had. To see where it’s at now? It’s a multi-billion dollar corporation.”

These days, Michael Jordan credits Spencer Haywood for being the first ballplayer of such stature to sign with Nike, paving the trail for his namesake multi-billion-dollar brand.

Haywood remains close friends with Nike athletes of multiple generations, supporting them through his story and his own on-foot endorsement.

“I wear some LeBrons, but most of my shoes are KDs,” Haywood said. “You always try to get equity, but Nike is my brand and it is who I am. All of my favorite guys wear Nike and I’m still a Nike guy.”

As LeBron and Durant don Nikes with their own logos on them and benefit from extra years of pro basketball (and the checks that come with it), so much of it is thanks to one man. Still speaking up on inequalities in the business of basketball and still friends with Phil Knight, Spencer Haywood may not be basketball’s first billionaire, but every icon that’s followed has stood on his shoulders.