Timur Bekmambetov’s screenlife courtroom thriller is watchable and efficient, but its take on AI, justice, and surveillance feels thinner than its premise promises.

Movies about artificial intelligence often promise big questions about the future, but few are willing to slow down long enough to explore them.

Directed by Timur Bekmambetov, Mercy is a near-future sci-fi thriller told through the screenlife format, a style in which the story unfolds through digital interfaces like surveillance footage, video calls, bodycams, and screens layered on top of screens. Bekmambetov has made this approach his calling card, using it across projects like Unfriended and Searching. Here, he applies it to a courtroom thriller centered on artificial intelligence, criminal justice, and due process.

The concept is timely. The execution is mixed. Mercy is watchable and efficient, but it never fully earns the weight of its ideas.

A Predictable Plot

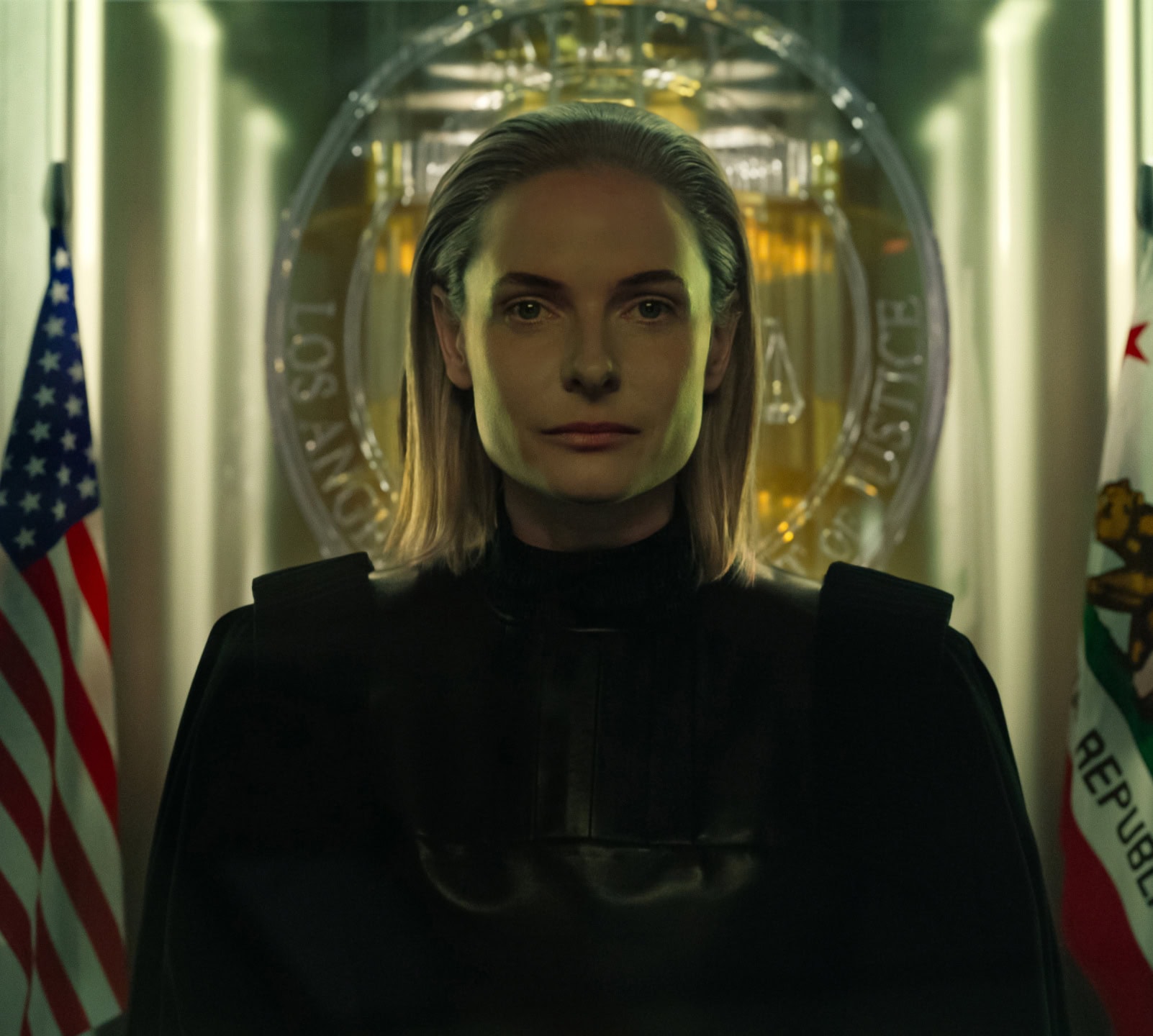

Set in 2029 — an oddly close future choice — Mercy follows Chris Raven (Chris Pratt), a police detective accused of murdering his wife. He wakes up strapped into the “Mercy Chair,” where defendants are presumed guilty and given 90 minutes to prove their innocence. His trial is overseen by Judge Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson), an artificial intelligence authority with access to virtually all digital records, footage, and personal data.

On paper, the premise is intriguing. In practice, the plot isn’t complex enough to justify the heavy use of screenlife. This format is most effective when the audience is forced to piece together fragmented information and sit with ambiguity. Here, evidence is presented clearly and often resolved too quickly. Instead of tension building, it flattens.

The worldbuilding also feels undercooked. For a film set only three years in the future, Mercy introduces a lot without fully explaining any of it. We see flying police vehicles, militarized city zones, and widespread surveillance. There are protests, red zones, and hints of social collapse. Some of that unrest appears tied to the AI justice system, but the film never makes it clear. These details feel more like set dressing than fully thought-out realities.

That vagueness extends to the AI court itself. The film frames this trial as a glimpse into the future of criminal due process, yet we’re told this is only the 18th case the system has handled. That undercuts the premise. Is this an experimental system? A rushed solution? A widely accepted norm? The film doesn’t decide, which makes the stakes harder to buy into.

One area where Mercy does succeed is its portrayal of data access. The film is blunt about it: Privacy is gone. The AI judge can pull from any camera, any file, any digital record. There are no boundaries. That depiction feels intentionally unsettling, especially in a world where conversations about data privacy are often softened or reassured away.

Still, the story is predictable. While the main antagonist isn’t immediately obvious through plot mechanics alone, the performance gives it away early. Rather than clever misdirection, the film relies on inevitability, which dulls its suspense.

Performance Check

Pratt is clearly constrained by the film’s concept, both physically and creatively. Much of Mercy asks him to remain seated, restrained, and reactive, carrying the story almost entirely through dialogue and facial response. While that confinement is meant to heighten tension, it instead exposes the limits of what the role allows him to do.

Pratt plays the character at a single emotional pitch for most of the runtime: urgent, defensive, and increasingly desperate. Those emotions make sense given the circumstances, but they didn’t feel layered or expansive. Over time, the repetition dulls its impact. What stood out most is how familiar the performance feels. I oddly felt like I’ve seen Pratt in this role before, not this exact scenario, but this version of him. A man under pressure. Wrongly accused. Fighting the clock. That sense of déjà vu isn’t a strength here. It makes the character feel less specific and less surprising.

He does what the role asks of him. The issue is that the role doesn’t ask much beyond endurance. Without moments of tonal variation, physical release, or emotional complexity, the performance stays functional rather than revealing.

Ferguson, by contrast, brings a sharper sense of control to Judge Maddox. She is the most consistent presence in the film, bringing a level of control and precision that many of the other performances lack. Ferguson’s delivery is steady, deliberate, and confident, and she feels fully in command of every scene she’s in, even when the film around her feels less certain of itself.

That sense of authority works in her favor. She doesn’t overplay the role or force emotion where it doesn’t belong. Instead, she approaches the character with restraint, which helps ground a film that otherwise leans heavily on digital chaos and surveillance imagery.

That said, I wasn’t fully convinced the character was distinctly futuristic. Judge Maddox often feels less like an advanced artificial intelligence and more like a hyper-efficient human authority figure. The performance works on a procedural level, but it rarely crosses into uncanny or unsettling territory; not because Ferguson falls short, but because the film’s vision of AI doesn’t push far enough.

That limitation becomes most apparent when the story hints that the AI may be developing something like consciousness. The turn doesn’t land. It feels rushed and underdeveloped, and the groundwork simply isn’t there to support it. Importantly, that failure rests with the script, not the performance. Ferguson does what she can with the material, but the idea itself never fully earns its moment.

In a film where control often feels theoretical, Ferguson is one of the few elements that actually delivers it.

Final Thoughts

Overall, Mercy is fine. It’s an easy watch, and the 90-minute runtime works in its favor. I never felt bored, and I appreciated that the movie didn’t try to stretch itself into something bigger than it needed to be.

That said, the screenlife format didn’t really add much for me this time around. It felt more like a familiar choice than a necessary one, and the story itself wasn’t complex enough to fully justify it. The ideas around AI, surveillance, and justice are interesting, but the film doesn’t spend enough time with them to make them feel truly thought-provoking.

I also never fully bought into the version of the future the movie presents. Some of the worldbuilding raised more questions than it answered, and a few of the bigger ideas felt underdeveloped. It all moved quickly, but sometimes a little too quickly.

In the end, Mercy is entertaining enough to sit through, but not memorable enough to stick with you. When it was over, I didn’t leave thinking deeply about the future of AI or justice; I was mostly just ready to step away from the screens.