Feeding the streets, charts, and the Internet, learn the business behind Lil Wayne’s apex album that sold over 1M copies in its first week.

In 2008, Lil Wayne was everywhere at once.

From Funkmaster Flex to Casey Kasem, rap’s rising rockstar was omnipresent and recession-proof thanks to a flood of free freestyles and an endless amount of paid features. Head in the clouds, feet in the studio, Wayne went on a run no one could keep up with and few could predict.

On June 10, 2008, he hit the metaphorical finish line for what felt like a three-year sprint: the retail release of Tha Carter III.

Selling over one million copies in its first week, The Martian made history in an era where even rap’s resident chart-toppers couldn’t conquer Billboard’s best.

Not only was Weezy F Baby doubling T.I., surpassing Jay Z, and outpacing Kanye, but he was also ending the year ahead of Coldplay, Taylor Swift, and Beyonce in the commercial category.

Defying the odds, market trends, and perhaps conventional wisdom, Tha Carter III debuted at No. 1 on Billboard during its opening week, doing damage typically reserved for N*SYNC and The Backstreet Boys.

It’s a feat only two rappers had accomplished before him and one no emcee has managed since.

On the heels of the album’s 15th anniversary, Boardroom breaks down the brand-building that went into making Wayne the breakthrough artist of Web 2.0 and the blueprint for every artist after him.

Allow Me to Reintroduce Myself

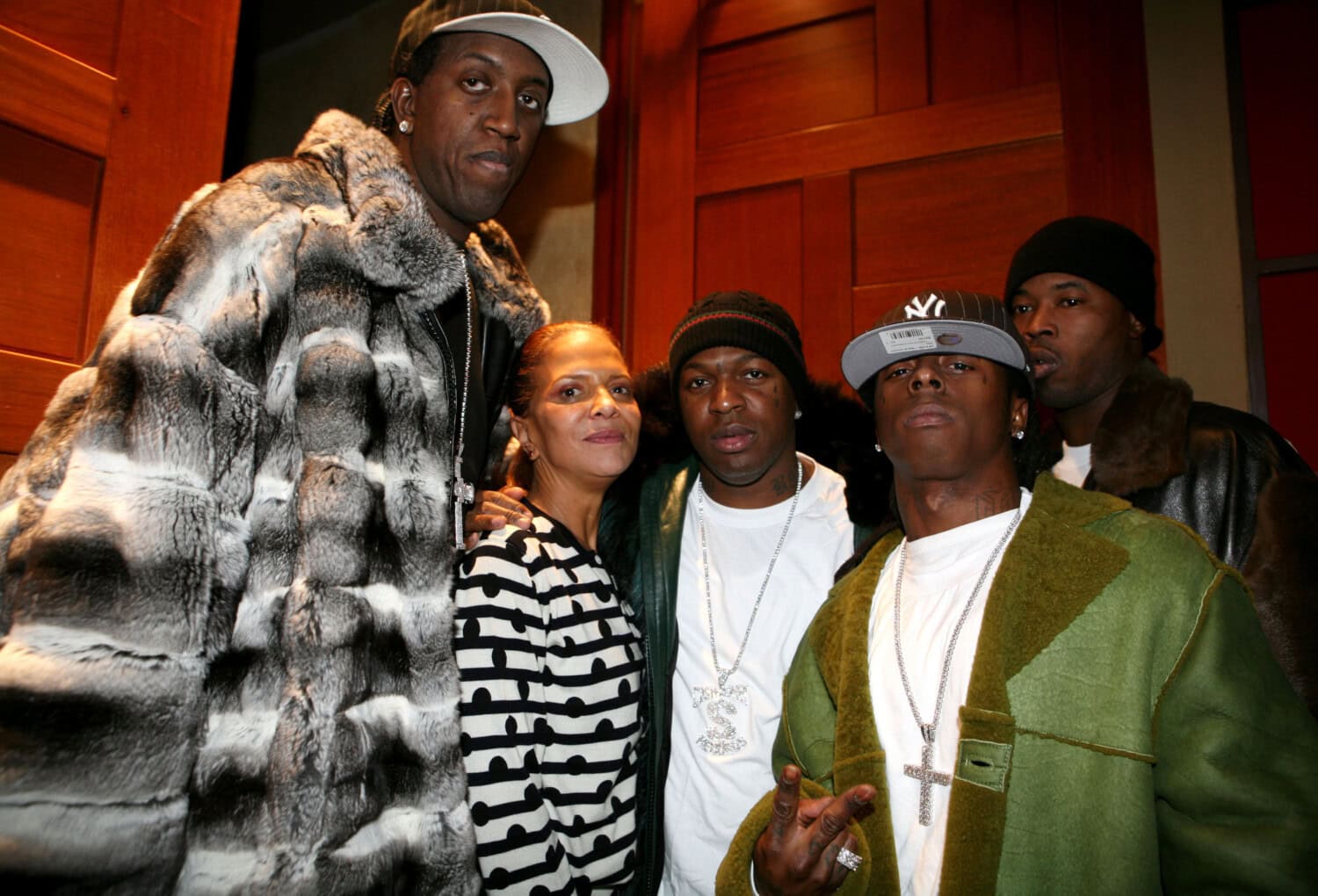

Lil Wayne was signed to Cash Money Records at the tender age of 12, too young for braces let alone permanent diamond teeth.

As Cash Money grew, so did Wayne with exposure on MTV, BET, and Billboard by age 16 in 1999. However, the early ’00s saw Cash Money’s momentum start to slow. Wayne, on the contrary, did not.

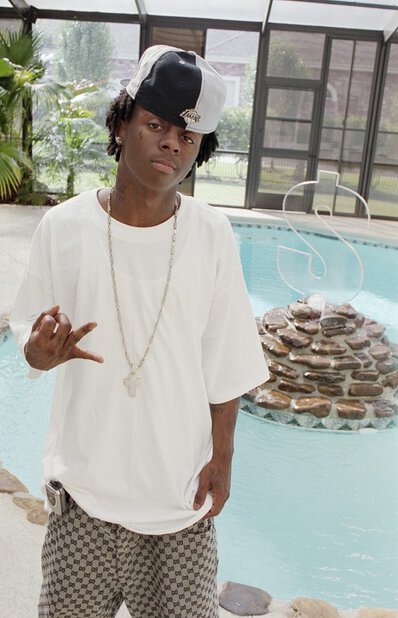

By 2004, Wayne was old enough to drink and established enough to steer his own career. He rerouted his raps and his branding with his fourth solo album: Tha Carter.

It debuted at No. 5 on Billboard, selling a solid 116,000 copies in its first week.

“It was the start of a path that I was able to create,” Wayne said recently on All The Smoke. “A path that deserved to extend. It was a maturity thing for me. I work all damn day every day but when we get one? It’s for a Carter and nothing else. I set a standard with that album.”

Through Tha Carter, Wayne emerged as the focal point of Cash Money. So much so that the label allowed its franchise player, Juvenile, to walk, tossing the keys to the castle to its 21-year-old talent. No longer would Weezy have to beat BG or Turk to the studio for first dibs on a Mannie Fresh beat, they were all his and his alone.

From BET countdown shows to layup lines at high school basketball games, Tha Carter‘s second single “Go DJ” resolidified Wayne as a solo star who could hold his own and make a hit. It was Wayne’s most successful song at the time, going two-time Platinum commercially while reviving his brand culturally.

At the same time Tha Carter was gaining traction in stores, Mannie Fresh wasn’t seeing his share of the royalties from his work. The architect behind almost all of the label’s greatest hits dipped to Def Jam, taking his bounce beats to Wayne’s biggest competition in the South, T.I. and Young Jeezy.

Artistically, Cash Money’s golden child was all alone.

Not even old enough to rent a car, Wayne was expected to carry a family business with raised expectations and less in-house talent. Fresh’s departure washed away the first draft of Tha Carter II. To make matters worse, Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in the same season the label was starting the album’s rollout.

Rather than roll over, Wayne lifted a ragtag bunch of producers, engineers, and songwriters from New York and Florida for Tha Carter II.

Selling off the strength of “Fireman,” Wayne debuted at No. 2 on Billboard, doubling his predecessor’s week one performance by selling 240,000 copies upon entrance.

Not only would Wayne defy the odds with his back against the wall but he’d introduce the world to The Runners, Deezle, DVLP, Big D, and Robin Thicke while bringing The Heatmakerz to the South.

From Soundscan to streaming, Tha Carter II would eventually hit two-time Platinum heights, making the 2005 triumph his biggest album at that time. It also introduced new elements of Wayne’s personality that would play out in years to come from the island influences of “Mo Fire” to the hustler rebrand of “D Boy.”

While all alluded to imagination and versatility that’d make him both beloved and attacked, it was the album’s seventh track that signaled what was next.

“Best Rapper Alive,” a goliath of an album cut not sold as a single, saw Wayne claiming his spot on hip-hop’s talked-about totem poll over a rock and roll-inspired beat. Doubling down on that notion, he closed Tha Carter II with the following last words:

Chaperone of the South, I got my coast

Yeah, and until I die

I’m the, the-the, the-the, the Best Rapper Alive

From entering himself into the conversation to becoming the conversation in years to come, Wayne was inverting an industry and a genre stylistically, sonically, and geographically.

At that time, the South was run by snap music — a place Wayne didn’t fit in — while New York called the shots on who was the top emcee.

Listening exclusively to Jay Z while subtly paying tribute to Hov’s Life & Times album art on each Carter installment, Wayne plotted a path to dethrone his hero — but not by the battle tactics that took careers and sometimes lives. Rather, Wayne was going to work harder than anyone else out there.

At the same time, Hov was working smarter, not harder. The emcee-turned-mogul looked to sign Wayne amidst his early ascent, paving a way for his own retirement while firming his grip through the pen of a young talent.

Famously, Jay Z lowballed Wayne on the offer with Cash Money co-founder Bryan “Baby” Williams catching wind of perceived tampering.

In an odd turn of events, Baby bet the house once again on Wayne, protecting and propelling his surrogate son at all costs.

Even expenses the shrewdest of businessmen near not consider.

Where the Cash At?

Like any entrepreneur looking to make it in hip-hop during the early ’90s, Bryan “Baby” Williams, aka Birdman, had lived the American Dream of sorts.

The New Orleans mogul had gone from selling CDs out of his trunk to moving units by the boatload at Best Buy, backed by a $30 million deal with Universal Music Group in 1998.

Already established and catching his second wind with Tha Carter series, there was no reason for Birdman to give Wayne’s music away for free. However, that’s exactly what they did.

Starting in 2003 and exploding in the years to follow, Lil Wayne began releasing a series of free mixtapes.

Some were promotional projects meant to shine a light on Cash Money act, Sqad Up, but projects such as Da Drought and The Prefix positioned Wayne as a rapper who could rip apart beats bested by each coast.

“The first one I did was just getting the okay from Baby that I could put it out,” Wayne said on ATS. “We were giving that shit out for free so that was the thing about Wayne. Wayne is always free!”

With no need to drop $15 at Best Buy but only needing access to an Internet modem, Wayne was creating fanfare across the country by giving out his renditions of Rap City favorites for no money at all. He was both Robin Hood and a prolific pirate all at once, ripping the hottest songs in all of hip-hop both literally and figuratively.

“My approach to mixtapes was always different,” continued Wayne. “I thought it was supposed to be you wanting to hear me on the songs that are out that I’m not on. 10 of the hot-ass songs that you’re banging in the club? I’m about to kill those for you. I’m gonna use the same melodies but flip the words and make it fun and interesting.”

By 2006, fans had tons of new Wayne music even if there wasn’t a new Carter album.

Better than that, they had accessible proof that The Best Rapper Alive was in fact Lil Wayne, considering he’d outdone everyone from Three 6 Mafia to Rich Boy on their own tracks.

From Dipset to Kanye, Slim Thug to Snoop Dogg, Wayne was reworking anything and everything at a rate no one could compete with dare alone try.

He was winning the world over, but to be taken seriously by the streets of New York, NahRight comment sections, and industry tastemakers he had to top Jay Z.

Rapping over Jay Z’s comeback single, “Show Me What You Got,” Wayne introduced the world — and no particular audience — to his evolved flow that was as adaptable as it was unpredictable.

The East Coast immediately took notice.

“It was like Wayne had this overnight transformation into this god-level MC,” Just Blaze, the producer behind the Hov single, told Boardroom in 2022. “A lot of people looked to that era as he was maturing. I was definitely impressed when I heard it. I was very surprised because I always thought Wayne could rhyme, but I had never heard him rhyme like that.”

From Family Guy-level punchlines to showcasing a voice that could be commissioned for hooks, Wayne’s restless unpaid internship on the Internet was getting him noticed.

Soon, it was going to get him rich.

Verses for Hire

In 2006, Lil Wayne was out-rapping the best MCs in the game for free on his own mixtapes.

In 2007, he was about to cash in on all that equity, using every square inch of the Internet and rap radio as a canvas for Tha Carter III build-up.

Claiming to have recorded a thousand guest verses in 2007 alone, Wayne appeared on singles for the likes of Mya, DJ Khaled, Wyclef Jean, and more as fans awaited a formal follow-up to Tha Carter II.

What they got was the ultimate appetizer as Wayne continued to release free mixtapes while scoring a cameo fee on at least 100 formal features in that year alone.

“I was only acknowledged for 77 of ’em,” Wayne told Missy Elliott. “I remember being able to get in my car, turn the radio on, I don’t care if I got the station wrong and switched to a pop station by mistake, I’m still on that motherfucker.”

Throughout the course of hip-hop history, artists have exchanged verses and appeared on tracks as a marketing move. Whether the spirit of competition, collaboration, or capitalism, the best of the best have excelled in the feature game, but none like Lil Wayne in 2007.

Even at their commercial heights, rap’s resident Billboard ballers did not work the game with the breadth or depth of Wayne.

Aftermath artists 50 Cent and Eminem rarely released more than a dozen guest verses in a given year, mostly made to live on other G Unit or Shady Records projects as a way to propel their own label’s sales.

Even Jay Z, the most marketing-savvy songwriter in rap, would rarely top out at over 20 features annually, with some sent to radio for R&B audiences but most made to move Roc-a-Fella units.

Wayne was born differently and worked differently. More importantly, he saw that times were different.

Most important? It was fast money.

For four years straight, Wayne had been rifling off verses strictly off the strength of keeping his name and his pen hot. Without pay or prompt, he could adapt his flow and tones to anything climbing club charts or touching the Top 40.

“Features usually come with a subject,” Wayne told ATS. “When you give me a subject it’s like school: I’m gonna finish the work first. Nothing’s easy but those are pretty convenient for me.”

Now with heat around his name and an appetite for his voice, Wayne could charge anyone from Gorilla Zoe to Enrique Iglesias up to $100,000 for a feature. Wayne’s range and expanding audience allowed him to remain relevant to all walks of life with his pockets padded.

“I wouldn’t do a song for my sister for less than $75,000,” Wayne told Rolling Stone in 2008. “Recording is an addiction. I can’t stop.”

Because of all this, Wayne’s name and voice had a buzz unlike anyone else in the industry. What he didn’t have was a proper album for sale.

While it was on Wayne to record, it was upon his label to parcel through thousands of verses and an impossible amount of beats to turn all of the promises of Tha Carter III into retail reality.

After all, Wayne wasn’t going to help — he was too busy working.

“I just come up with good songs,” Wayne told Rolling Stone. “It’s up to [Universal Records] to figure out what goes on. I don’t want that headache.”

Leverage & Leaning In

For three straight years, Wayne had been recording non-stop.

Unlike Tha Carter II, Wayne was now fielding beats by the likes of Kanye West, Swizz Beatz, and will.i.am. It was overwhelming for all involved, including the man making the majority of the music.

“As far as my shit? You have to stop me and say, ‘Tune, we need x amount of songs on by this date,'” Wayne told ATS. “And I let them pick them because I can’t.”

On March 13, 2008, Universal Music Group made their pick.

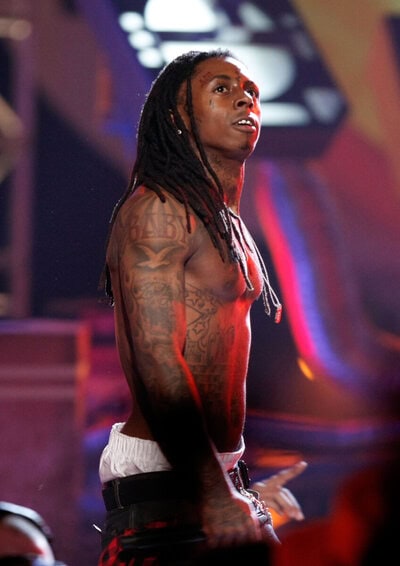

Going all in on a pop crossover, UMG chose “Lollipop” as the album’s first single. After years of proving himself as The Best Rapper Alive, Wayne was now crooning over autotune and playing guitar with Static Major by his side.

Shocking all audiences, it absolutely worked. For five straight weeks, “Lollipop” topped the Billboard Hot 100, selling over two million in ringtones alone. At the same time, UMG was updating his MySpace page — the most popular in music — every day to feed fans awaiting Tha Carter III.

Still, Wayne was attempting to put out a physical album in an increasingly fickle landscape. Globally, music sales had hit a 20-year low in 2008. On top of that, fans were used to getting an abundance of his music for less than a penny. Would they be willing to shell out $14?

“He has literally given away hundreds of songs,” Danyel Smith, then Editor in Chief of Vibe Magazine, told The LA Times in 2008. “Here is someone who has given [fans] so much music for free that they want to support him.”

And support they did.

On June 10, 2008, Tha Carter III was released after years of leaks and delays. It sold over one million copies in its first week, providing a surge to the entire industry and cementing Wayne.

“This is a landmark week for Lil Wayne and for our company,” Sylvia Rhone, then Universal Motown President, said in a press release at the time. “Wayne has not only scored by far the biggest debut of the year, but the highest first-week sales in Universal Motown history. This is an event release from a genius artist who represents and speaks for youth culture.”

In Wayne, hip-hop had the superstar he proclaimed to be before he was.

In the industry, both labels and artists had a new formula they could look to recreate. Wayne’s week one numbers were so big that 62 other albums on the chart saw a 10% or more sales increase off his energy alone.

There was one problem: could anyone duplicate the pace and production of Lil Wayne?

“Wayne has been super-serving his audience,” Rhone said. “He’s not your average artist, so it’s hard to make a model based on Wayne. You look at the elite — Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, Prince — he’s on that level. He is touring 365 days a year and in the studio 365 nights a year. Not many people can pull that off.”

Prophetic in the moment, Rhone was right. Since Tha Carter III, no rapper has sold over one million albums in its opening week.

Just the same, it hasn’t stopped plenty from trying.

A New Model, A New Era

Lil Wayne is a generational talent, backed and nurtured by one of rap’s most powerful moguls.

Though no artist since Wayne has been able to be in as many places at once where output is concerned, different elements of his formula for success have been adopted by all of today’s top talent.

When it comes to flooding the market with material, Youngboy Never Broke Again is akin to Wayne in regard to Internet excess, releasing 26 mixtapes since 2015. Like Wayne, Youngboy has fed fans for free while still scoring Platinum plaques on formal releases.

More common in modern marketing, the feature formula for commercial success both on the radio and in the bank has been adopted by just about every artist with a buzz. To a tee, this strategy has been played perfectly by Drake. Similar to Wayne, Drake has been able to appear on other artists’ singles as a way to remain relevant in constant rotation.

Upping the ante, he used his peak years as a means of making songs released by peers of his own, hopping on remixes in official fashions that felt at first like freestyles but quickly placed him in emerging markets.

Perhaps most endearing was Wayne’s ability to get better when most rappers either give in or sell out. Despite being only 25 years old when Tha Carter III was released, Wayne was a 13-year veteran in the industry. In a genre where most emcees peak critically on their first album and commercially shortly after, Wayne had the backing of Baby and the belief in himself to hit new heights when he was no longer new.

One could say Lil Durk has taken direction from the same climb, coming into fame off the strength of a booming Chicago scene but outlasting larger stars simply by sticking to it.

To this day, the Wayne formula of flooding the market with features and mixtapes has been borrowed by all of hip-hop’s top talent in some fashion. In many ways, artists such as Future, Young Thug, and Travis Scott have stolen pages from the same playbook, each having Wayne’s DNA in their own ascents.

Though no one has seen the same sales success in hip-hop since Tha Carter III in 2008, Wayne’s remained inspirational as an artist and perhaps underrated as an executive. His sole focus on writing and recording has allowed him to tour the world and release new music, still serving as a sought feature.

As Wayne works away on Tha Carter VI, times are different but eerily the same.

The advent of AI poses threats and opportunities to the business of art while a writer’s strike and abundance of content makes one wonder what can connect in such a crowded, confusing space. If history has taught us anything, Wayne works best in a drought and thrives in chaos.

He did it before when no one saw it coming, perhaps he’ll do it again.