What happened when Rafer Alston left behind his local legend status in NYC to carve out a career in California.

By the time Rafer Alston was 15, his game was known across New York City. Hoop whisperers from Brooklyn to Harlem knew of the flashy kid from Queens, even if they didn’t know his actual name. As an adolescent, Rafer was simply known as Skip by NBA elite and EBC competitors.

“Most legends are legends at the end,” Cardozo High School head coach Ron Naclerio told Boardroom. “Rafer was a legend before it even began.”

Despite earning envy from an audience of millions of New Yorkers, Rafer “Skip to My Lou” Alston traveled from South Jamaica to Southern California with a ball and a dream.

So, why did Skip leave the place where everyone knew his name?

“Tarkanian,” Rafer Alston told Boardroom. “The dream of being recruited by Coach Tark and wanting to play for him.”

Madness in the Mecca

As a kid, Alston fantasized about balling in his backyard for Lou Carnesecca at St. John’s or putting on the kente cloth for John Thompson at Georgetown. Years before either coach would write him a letter, he met his first formal mentor by hopping the train to Harlem.

“The first time I saw Rafer at the Rucker, the place was packed, and there were no barriers yet, so the sideline was the crowd,” Naclerio recalled.

Already a local legend at Cardozo High School in Queens, Coach Naclerio returned from a timeout in a heated men’s run to see two teenagers trying to sneak their way into the action.

“It was 12-year-old Stephon Marbury and 13-year-old Rafer Alston,” Naclerio added, laughing. “Rafer comes back the next game; we throw him a uniform and put him against grown men.”

Suiting up alongside Naclerio at the Rucker, Alston quickly earned nicknames like “The Energizer” and “Shorty” due to his small stature and frenetic defense. Rafer’s confidence grew faster than his legs, though, setting the stage for a moment that’d shape the rest of his life.

“I throw the ball to Rafer, and he’s trapped in the corner,” Naclerio recalled about a game he played at Rucker Park. “I cut to the middle to get the return pass, but I had to run around a fat ref, and I stumbled. As I get up, I start hearing the crowd because Rafer got out of the trap!

“The two guys are chasing him, Rafer starts bouncing the ball as only Rafer can do, and he starts skipping!” he continued. “The announcer, Duke Tango, goes, ‘Skip, skip, skip to my Lou!’”

At the moment, a new nickname was born.

Despite clamoring from coaches all over the city, Rafer stayed faithful to Cardozo. As a freshman, he hit Lincoln High School for double digits off the bench in barely 10 minutes of play. Old enough to start in his second season, his star increased ten-fold.

“Sophmore year he plays the whole year, averages 25.5 points and 8.3 assists,” Naclerio notes. “He made All-Queens and starts getting all the notoriety.”

All the notoriety meant attention from the girls and recruitment from the Supreme Team. Distractions off the court and adversity at home started steering Skip away from school, affecting his sleep schedule and depleting his eligibility. Over the course of his junior and senior seasons, he played 10 total games, with the lows more memorable than the highs.

One includes Rafer crying his eyes out in the first row in the stands during a showdown between Cardozo and the Stephon Marbury-led Lincoln High. The Georgia Tech-bound Marbury went on to beat Naclerio’s squad in a close game. All Rafer could do was watch.

Around that same stretch, Scott Perry from the University of Michigan came to recruit Rafer in person. The only problem? He couldn’t play. Had he been eligible, Rafer could’ve been the successor to Jalen Rose in Ann Arbor, playing in front of packed arenas on national television.

Instead, he had to go back to the park to prove his worth.

“Ron, what did he do?!”

“Tark called me wanting Marbury,” Naclerio said. “I said, ‘Listen, I’ve got the next best thing.’”

Flying all the way from Fresno to New York, Jerry Tarkanian joined Naclerio to watch Rafer play at Rucker Park.

As the game started and the crowd quieted, the player Tark flew across the country to see was nowhere to be found.

“Where’s Rafer?” the college coach asked.

“Don’t worry about it,” his high school coach answered.

Over the course of the first half, the two coaches went through that exact exchange about five times. Then suddenly, 17 minutes into the game, the star showed up to murmurs from the crowd.

Instantly, the person running the clock at Rucker Park called a timeout and threw Rafer a jersey. The crowd went nuts as Rafer took to the court, quickly getting warm through an array of nice moves and textbook defense. To start, according to Naclerio, he was “a basic, non-hot dog point guard.” But when a player on the other team called a timeout for a clear out, something ignited in Rafer.

Upon the iso, Rafer ripped the ball from the defender. He started skipping with the ball, turning the catcalls into cackles. From there, he weaved in and out of multiple defenders before throwing it around one’s back.

“He’s like Pearl Washington,” Naclerio said of the sequence. “Tark goes, ‘Ron, what did he do?’ He did a move he’d never seen.”

Despite coaching the likes of Greg Anthony and Larry Johnson, Tark was not just smitten by Skip, he was perplexed.

“After the game, Rafer has all the girls coming at him, it’s ridiculous. Tark goes, ‘What do I have to do to get him?’”

Before Naclerio could answer him, his assistant at Cardozo, Billy Medley, stepped in.

“You leaving tonight? Take him with you.”

The Path Less Traveled

For the next three summers, Rafer was removed from the fanfare and pitfalls of South Jamaica while in Fresno. Playing at Ventura City College and Fresno City College, two JUCOs that allowed Rafer to get his grades right, Tark took training seriously before his prized point guard was enrolled at his school.

“Summers in Fresno were hot and brutal,” Alston said. “But we worked hard. One thing about Coach Tark was he made sure that you stayed in the gym and got stronger. It was just relentless work. My assistant coach at the time, John Welch, wouldn’t let up. Every day was conditioning with the battle ahead in mind. Tark’s biggest thing was to be prepared.”

All that preparation paid off. In Rafer’s JUCO debut, he scored two points and handed out 13 assists. More John Stockton than John Coltrane, the streetball artist was learning another approach to the game. All the while, he was hitting the weights and hitting Pauley Pavilion to test his skills at the infamous UCLA summer runs.

“Listen, the UCLA summer runs were amazing!” Alston said. “It was the who’s who of basketball as far as the players there. It was early in the morning, in your face, and you had to bring your A-game every day.”

Local legends ranging from Magic Johnson to Baron Davis danced with Skip in sparring sessions, making for some of the most competitive pickup play the world would ever witness.

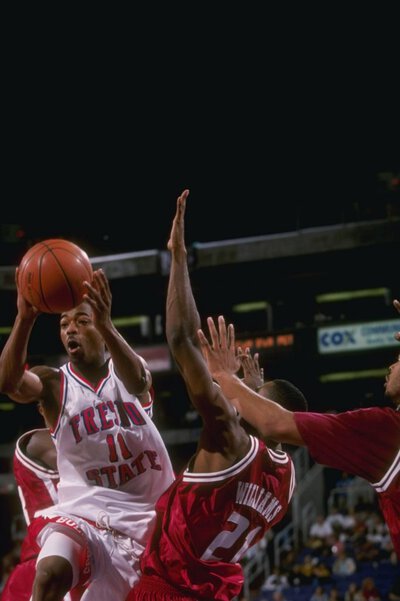

Though Rafer was inside LA’s most marveled run, he was on the outside looking in when it came to team play at that level. Finally, after three years of going at it with the game’s best at UCLA, navigating the local community college circuit, and running sprints for Coach Tark, it was time for Skip to make his national debut. That fall, he enrolled at Fresno State, where he was just another kid on campus.

“He had an Acura and was just a regular, chill dude,” Rick McCaster III, a Fresno State student at the time, told Boardroom. “You’d have never known he was the legend he was. I was in a fraternity, and he’d come to the parties. He wasn’t cocky, [and] he was down to earth.”

As the city of Fresno began to know Rafer, the world was about to meet Skip.

Cover Boy

In the fall of 1997, weeks before Rafer Alston ever played a Division I basketball game, he did something bigger.

The 20-year-old phenom covered SLAM magazine alongside the headline, “The Best Point Guard in the World.”

Around New York City, Rucker rivals and former foes were brooding with jealousy that the kid who hadn’t played a college game was covering a magazine. Around campus at Fresno State, the student body was starting to discover that Rafer had a history they knew nothing about.

“That SLAM magazine?” McCaster said. “Oh, he’s really that dude!”

Over the course of the 1997-98 NCAA season, Rafer ran a Bulldog offense that spawned four future NBA players. In fact, it almost had five. Infamously, Tark recruited Harlem hot-shot Tyron Evans to play at Fresno with Rafer. Around NYC and later at the EBC, Evans would be known worldwide as Alimoe, one of the greatest streetball showmen to ever play.

“He had a chance to come out,” Rafer reflected. “I wish he would have. It would’ve been a great tandem. I would’ve loved to see my boy that I grew up playing with and against come out there and play with me.”

Even without Evans, Rafer and Tark’s team rumbled to a 21-13 record. While Rafer’s game was more grown than at Rucker and his availability greater than that at Cardozo, the squad’s imbalance of brilliance and brouhaha made the season a rollercoaster.

“The team was nuts,” Naclerio said. “On a good day, they could beat Duke by 50. Then the next day, they’d lose by 30 because half of them would be high, arrested, or hungover.”

In Fresno, Rafer was convicted of assaulting two neighbors in 1998 while talented teammate Chris Herren missed the start of the season due to a failed drug test. All the while, Fox Sports was filming and running a documentary called Between the Madness that profiled the troubled team.

While re-runs relayed Rafer’s off-court issues, SportsCenter highlights began showcasing his potential on the court.

“Rafer showed some real flashes,” Naclerio said. “That Arkansas game was a big day. He opened up the NBA scouts’ eyes, but not enough.”

Battling against an Arkansas squad led by fellow NYC Point God Kareem Reid — a.k.a. The Best Kept Secret — Skip showed scouts he could lead a team of talent in a high-pressure matchup. With another year of eligibility and more All-Americans on the way, pro teams could see Skip’s maturity in real time, prepping him for a lottery land in the 1999 NBA Draft.

Once again, issues away from basketball altered his path.

Going Back to Cali?

Alston had turned Fresno State into a destination in only one season of Division I play, but he also had put his academic eligibility in peril that year.

Realizing he was unlikely to be eligible for his senior season as a Bulldog, Rafer had two choices: transfer to a D-II school or declare for the 1998 NBA Draft. Always willing to bet on himself, he did the latter, getting into the NBA Pre-Draft Camp at Moody Bible College.

“I wrote two letters to David Stern: one from his mother’s address, and one from his Fresno address,” Naclerio said.

In order to get Rafer’s name in the Draft, he raced to the post office to beat the midnight declaration deadline.

“I got there at 11:58 p.m. and got them to stamp it. On Thursday or Friday, the NBA announces the players declared for the draft, and we see Rafer. Now, we’ve got to get him into the camp.”

Over the course of the camp, everyone from Ernie Grunfeld to RC Buford sought out the Cardozo coach, asking about Rafer as a player and person. Naclerio spoke truthfully about his troubles. Across the league and even locally, teams wanted Rafer but had their concerns.

“The Knicks loved him,” Naclerio said. “But they were scared.”

As Alston impressed at camp in front of NBA coaches and general managers, a familiar face approached Alston about doing a private workout.

“The day of the draft, Rafer was going to fly from Fresno to the Lakers to work out in front of Jerry West for the second time,” Naclerio said.

Keep in mind, it was only two years prior that West worked out Kobe Bryant behind the scenes, brokering a Draft Day trade that’s now historic.

“People in the organization wanted to pick Rafer, but they ended up picking Tyronn Lue.”

Ultimately, Rafer’s talent took him to the Milwaukee Bucks, but his troubles slid him to the second round.

Legend in Two Games

Originally, 1998-99 was supposed to be Rafer’s senior season at Fresno State. Eventually, it was meant to be his rookie season for the Milwaukee Bucks. In reality, it ended up being his lone season in the CBA for the Idaho Stampede.

Far removed from the concrete clamor of New York or the sunny fanfare of Fresno, Rafer was once again working on his game with next to no one watching. Ironically at that time, everyone ended up watching what were essentially re-runs.

In 1999, AND1 released its first VHS mixtape, known in circles as “The Skip Tape.”

Consisting mostly of choppy footage of a teenage Rafer abusing ankles at Rucker Park and in NYC Pro-Ams, the archival Alston highlights took over the nation while only those in Idaho could see him play live. Prior to publishing, his Cardozo coach was already seeding copies.

“The original AND1 mixtapes? There’s ten or 12 tapes,” said Naclerio. “I know Billy Donovan very well. I sent them to Billy Donovan to watch, and he gave them to Jason Williams. That’s a fact. Billy will tell you.”

Around the country, the mixtapes made their way to the people by way of barbershops, sparking NYC-centric showmanship to basketball beyond the Big Apple.

“There was a good four-year period where I didn’t watch the NBA,” Compton native and former Fresno City College basketball player Travonne Edwards told Boardroom. “But AND1? To have that VHS? Rafer’s game was so influential as to how everyone approached it.”

“There was a point where I was getting benched for my turnovers because I was trying all this stuff. That’s how influential Rafer was.”

As Rafer’s legend grew through “The Skip Tape,” the stage was set for his February 2000 NBA debut in Milwaukee. In an era where the Internet was in its infancy, many fans thought the streetball star renowned as Skip to My Lou actually made it to the league thanks to his AND1 fame.

In many ways, it was actually escaping streetball that gave him his chance.

A Legacy Like No Other

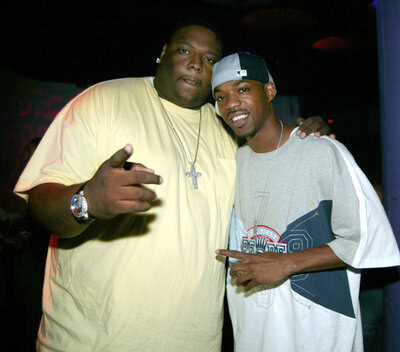

While Skip to My Lou lives on through endless inspiration and YouTube clips, Rafer Alston went on to have an 11-year NBA career that took him all the way to the Finals in 2009. Rucker Park play in New York City prepared him for packed stadiums in the league, while his tutelage under Tark in Fresno gave him the space and humility to master two styles of play.

While Fresno did lots for Rafer, it’s possible he did even more for Fresno.

“We were still University of California State Fresno,” McCaster said. “The growth of Fresno is because of players like him coming. People with superstar talent can come here and just be a student.”

Since then, the Bulldogs’ athletics program has grown in abundance. Shortly after “The Skip Tape” hit stores, Fresno State basketball became an AND1-sponsored school. In the years since, they’ve secured a Nike sponsorship and produced elite athletes such as Paul George and Aaron Judge.

While most people move to California to become famous, Rafer Alston wanted to escape fame.

“Walking with Rafer near Rucker is like strolling down Michigan Avenue with Michael Jordan,” Anthony McCarron wrote in Skip’s 1997 SLAM cover story. “When Rafer’s in a game, you can hear the oohs and aahs from blocks away.”

Even in 2022, the local love from SLAM and the national pedestal it placed his game on still hits home with Rafer in his residence in Houston where he coaches youth hoops.

“I take a glance at that picture every day before I leave the house,” Alston said. “That cover was the greatest feeling I had in my life.”

Growing up, the kid who idolized Isiah Thomas and hopped on the subway to sneak onto Harlem’s holy ground became a local celebrity thanks to a handle that was part Pete Maravich and part Pete Rock. While his high school career collapsed due to poor attendance, it provided the foundation for securing a scholarship, entering the NBA Draft, and creating a livelihood for himself and his family.

“Cardozo Basketball with Mike Bell, Billy Medley, and the blessing of his mom, became a village fighting the negative influences in Rafer’s life to end up a positive,” Naclerio said. “The problem is we had to do it on Rafer’s home court, which was South Jamaica. There was a lot going on in the ’80s and ’90s.”

Urban legend, NBA vet, Alston holds a special place in hoops history and an even more unique spot in his coach’s heart.

“Rafer’s like a son to me.”