Learn how one of New York City’s most revered Point Gods had top sneaker companies competing for his likeness years before he was a pro.

Almost exactly a year ago, the landscape of amateur sports was changed forever.

With the introduction of NIL (name, image, and likeness), college kids and prep prospects in football, basketball, and beyond were suddenly able to earn endorsements while still retaining NCAA eligibility.

Almost instantaneously, the world of recruiting shifted, with talented teenagers becoming millionaires overnight.

While college basketball has long been run by sportswear companies, amateur athletes like Paolo Banchero and Azzi Fudd finessed the system by earning endorsement deals outside of their school sponsorships with the likes of JD Sports and Curry Brand.

Though the college kids at all-time hoops institutions broke the mold with their NIL bags, it was a storied Point God from Brooklyn, NY who laid the foundation for athlete leverage among institutions and big brands almost 40 years prior.

“There was a Pro-Keds rep that approached me about wearing their sneakers when I was in high school,” Pearl Washington recalled in Bobbito Garcia’s book, Where’d You Get Those. “With the understanding that when I left college to go pro, they would be interested in signing me to an endorsement contract.”

Famous for years around New York, the prep named Pearl had all the clout when it came to making moves.

The Battle of the Stars

The date was Dec. 10, 1983, in snowy Syracuse.

Despite temperatures hovering between frigid and freezing, fans flocked from far and wide to watch basketball’s best battle for bragging rights and perhaps sneaker deals.

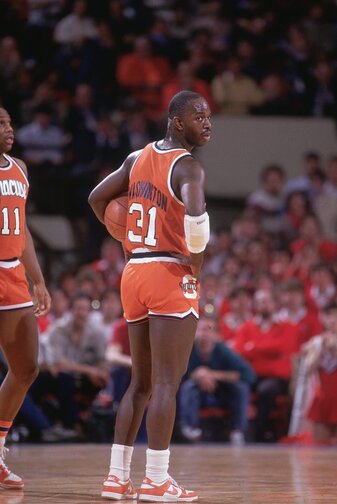

With snow on the ground and high tops on their feet, New York’s No. 1 point guard, Pearl Washington, hosted the nation’s No. 1 team, North Carolina. Coming off Dean Smith’s first title run and led by a sophomore standout named Mike Jordan, the Tar Heels took to the Carrier Dome to play in front of 32,235 screaming fans.

Across the court, the city’s second-ranked prep point guard, UNC freshman Kenny Smith, had the tall order of guarding the Pearl in his own house. Clad in Converse and powder blue shorts, Smith thought he’d have a tougher time defending Pearl than his GOAT-status shooting guard teammate.

“I thought I could guard Michael Jordan, because I guarded Pearl Washington,” Kenny Smith says in NYC POINT GODS.

Strapped up in high-top, team-issued Nike Air Force 1 Highs, Pearl pushed the rock for the Orange as MJ and Kenny chased him. When it was all over, Mike won the battle, bringing home a victory for the visiting Tar Heels.

However, in the world of shoe supremacy, Pearl came away the winner.

See, before Mike was the face, feet, and logo for Nike’s multi-billion-dollar subsidiary named after his image, he was a die-hard Adidas fan.

Despite attending a Converse college, Mike loved the Three Stripes so much that he wore them in practice and while walking Chapel Hill’s campus.

For all of Mike’s talent and appeal from giving Dean Smith his first National Championship, the decorated coach wouldn’t let his star play rock the rival brand on the court.

For Pearl at Syracuse, it was different, because, well, Pearl was different.

After a high school career that saw him pulling up to games in full-length fur coats and captivating crowds from gymnasium to park, Pearl was a local celebrity that rivaled rappers and even those on the New York Knicks.

Leading a loaded New York City Class of ’83, it was Pearl that proved superior to all other Point Gods that’d eventually go pro.

“He was so good that when I visited Syracuse University, I told them I wanted to come,” former NBA All-Star Mark Jackson told Boardroom.

“Jim Boeheim says, ‘If I was you, I wouldn’t come.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘Because we’ve got Pearl Washington.’ That’s how great Pearl Washington was.”

With greatness came power and influence.

That’s why in the spring of Pearl’s freshman season at Syracuse, he had the leverage to persuade Boeheim to let him play in Pro-Keds, despite Boeheim’s brand deal with Nike. In reality, Pro-Keds had been courting Pearl since his senior season at Brooklyn Boys and Girls High School.

“Pearl Washington was so into sneakers that his freshman year at Syracuse he wanted to wear his Pro-Keds instead of the team-sponsored Nikes,” Tony Bruin recalled in Garcia’s book. “He was the first player Coach Jim Boeheim allowed to wear whatever he wanted.”

Because of Pearl’s swagger and game, he rocked the aptly named Pro-Keds Competitor in white and orange nylon mesh for the Big East Tournament.

Conversely, his peers played in Nike Air Force 1s and Nike Air Legends that placed paper in the pockets of their college coaches, but did little to build their own bucks or their own brand.

The stage for Pearl and Pro-Keds was humongous.

At its height in the ’80s, the Big East Tournament was played in Madison Square Garden and at the time was broadcast on ESPN.

Because of this, both Pearl and his Pro-Keds sneakers were showcased to a massive audience both locally and nationally.

Around the city, Pro-Keds was already a big deal, both in the parks and in the streets, despite Converse and Nike owning most of the market share in college basketball.

“Willis Reed started wearing Pro-Keds back in his early days,” Basketball Hall of Famer Nancy Lieberman told Boardroom. “It was Pro-Keds and canvas Converse. Those were the shoes that we grew up on.”

In an era where college coaches were paid directly by sneaker brands, Pearl Washington had the cache and clout to upend it all.

Moreover, he did it all en route to an All-Tournament Team performance where he absolutely abused John Thompson’s infamous full-court press.

In the championship game, Pearl led all scorers with 27 points and six assists, giving Pro-Keds the ultimate endorsement on what was then basketball’s biggest platform.

Fans of all ages took note, especially the next generation.

As Kenny Anderson put it bluntly in NYC POINT GODS, “he’s the God.”

Ahead of His Time

While Pearl put Pro-Keds on the national map, a world without NIL kept him from being formally paid as an amateur, where legalities are concerned.

“It was only a verbal agreement,” Pearl wrote in Garcia’s book. “[The rep] left Pro-Keds, so the contract never materialized.”

In a sense, what Pearl did for Pro-Keds in college was not much different than the visibility LeBron James gave Adidas while in high school.

In later years at Syracuse, the Brownsville baller continued to own the Big East, making numerous All-American teams and filling up the Carrier Dome. He’d do most of his damage in Nike, donning Dunks in both high and low-top fashion that still fetch a pretty penny in 2022.

Making money for both Pro-Keds and Nike over the course of his career at Syracuse, the Point God with pork chop sideburns and sizzling spin moves never got the checks he deserved from either brand nor did his spiritual successors.

“I wouldn’t have had to play in the league,” Anderson said when asked how his career would’ve been had NIL existed in his amateur era. “I’d have my money. I was the biggest in the city in high school, I would’ve made so much money it’d be ridiculous.”

When Pearl turned pro in 1986, Avia scooped him up for a five-year deal worth $125K.

By that time, the boy named Mike Jordan was now the man at Nike, making quadruple that of Pearl’s paper through footwear alone, said to start at $500,000 per year, plus royalties.

Additionally, it’s reported that Avia originally wanted Len Bias, another Nike school product. Bias signed with Reebok right before that infamous 1986 NBA Draft night.

As a New Jersey Net, Pearl played in Avia in front of another major, local market. It’s said that the brand was as big on Pearl’s play and growing star as they were the idea of selling his nickname.

Sadly, Pearl’s NBA career was short in contrast to his contemporaries, though his legend still holds up.

To this day, John Stockton considers Pearl the toughest player he’s ever had to guard, while God Shammgod says he’s the last Point God he’d ever want to defend. Even after his passing in 2016, icons from New York and beyond regard Pearl with the highest of praise.

“Pearl Washington was the ultimate point guard,” Lieberman said. “Big, strong, aggressive, and would come at you. You looked at the schedule and went, ‘I’ve gotta play him? No.’ He was gonna win that war. His handles were great, but he also made everyone around him better.”

Among Brooklynites, the folklore surrounding Pearl is passed down from generation to generation.

“Pearl Washington influenced my dad growing up. My dad is from Fort Greene, so I learned a lot from him because he spoke highly of Pearl,” Smush Parker told Boardroom.

As the 2022-23 NCAA season approaches, Syracuse remains a Nike school, with Pearl’s famous No. 31 hanging from the rafters in the arena now called the JMA Wireless Dome.

Kids today may have the leverage to sign deals in college, but they still don’t have the leverage to play in competitor brands like Pearl.