A deep run in the men’s NCAA Tournament means a big payday for that team and its conference. For now, that’s not the case in the women’s tournament.

It was a banner year for University of Miami basketball. Literally, if the Canes raise banners for Final Four appearances.

Its men’s basketball team advanced to the Final Four for the first time in school history this year, while its women’s team went all the way to the Elite Eight as a 9 seed. The result is a nice financial boost for the Miami athletic department. The men played in five tournament games, which earned them five distribution units from the NCAA’s Basketball Performance Fund. Each game played means one such unit for a school’s conference, awarded annually for six years.

Last year, each unit was worth $338,887, so expect 2023 units to be a touch higher. Multiply that by five (one for each Miami game) and then by six (one for each year it is paid out), and Miami men’s basketball made $10.1 million for the ACC this season. If the league distributes that equally, Miami can expect a total of $667,774 for its efforts — and that’s before taking into account other ACC teams’ success this year and others over a six-year period.

It’s a nice payday, even for a school in a so-called power conference that has a lucrative TV deal as well.

The Miami women appeared in four tournament games this year. For their efforts, the university will see $0 from the NCAA’s Basketball Performance Fund.

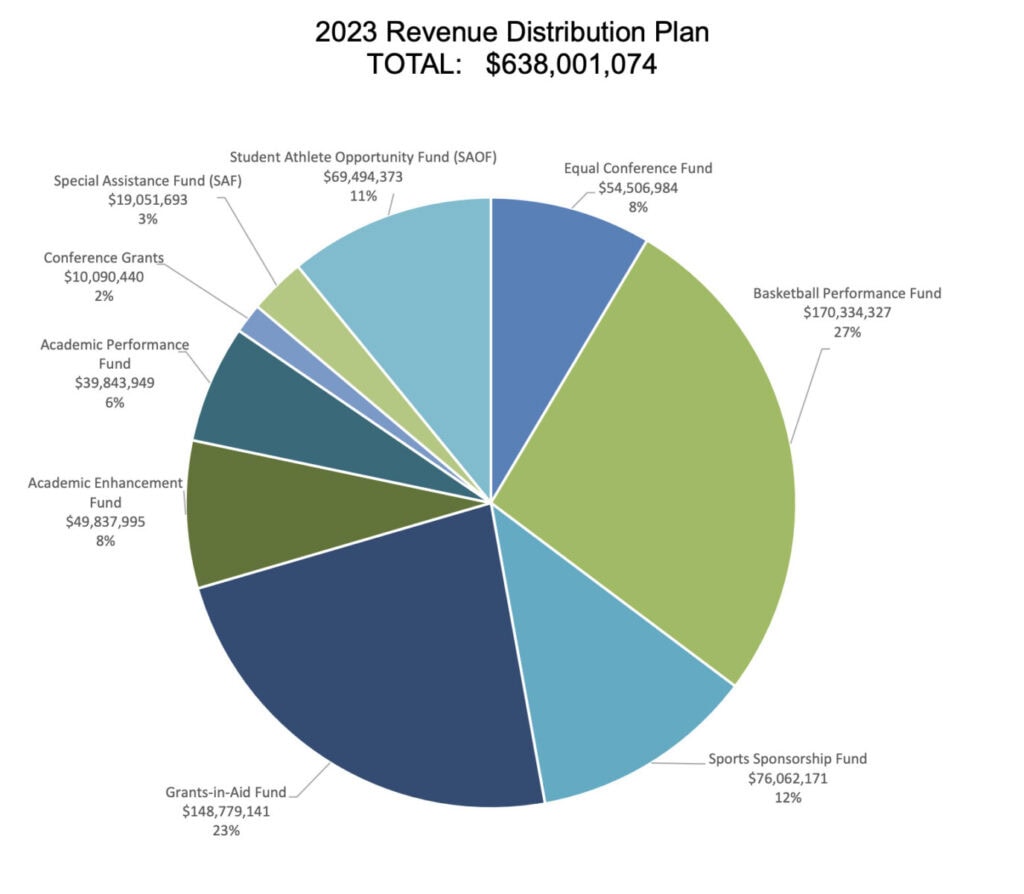

That’s because the Basketball Performance Fund (which you’ll notice is not called the Men’s Basketball Performance Fund) only pays out based on performance in men’s basketball tournament games. It’s a significant amount, too. In 2023, the NCAA will distribute more than $638 million to its schools — 27% of that tied directly to a conference’s men’s NCAA Tournament performance.

No such fund exists for the women, which Knight Commission CEO Amy Privette Perko believes goes against the very principles on which the NCAA supposedly stands.

“It is inconsistent with the NCAA’s constitutional principle of operating in a gender-equitable way,” she told Boardroom. “The NCAA just needs to put its constitutional principles into practice.”

The Knight Commission is an independent group that focuses on leading transformational change in college athletics. Its mission is to prioritize student-athlete education, health, safety, and success. As a think tank with no formal partnership with the NCAA, the Knight Commission doesn’t have the authority to enact change. It is, however, made up of former university presidents, athletes, and other experts in their field.

To show the commission’s influence, Perko points to the academic component of the NCAA’s revenue distribution. On the commission’s recommendation, the NCAA has added an academic performance unit, coming directly from the money it makes in its men’s basketball TV deal with Turner. Schools can be eligible to receive this unit by meeting one of a series of benchmarks, meant to level the playing field so that the academic rigor or resources available at an institution do not create an unfair disadvantage.

It’s all to say that the Knight Commission can have a major impact on NCAA policy. Yet, here we are, more than 500 days since the NCAA’s External Gender Equity Review (otherwise known as the Kaplan Report) recommended the NCAA deliver distribution units based on women’s basketball postseason performance as well. The NCAA has made no visible progress on that front, and it’s a point of frustration for Perko.

“It didn’t take them long to make a lot of changes to bring the tournament experience up to par,” she said. “So it is discouraging that it has taken them this long.”

And while there hasn’t been much progress to date, there’s reason for hope. The NCAA’s deal with ESPN for its Division I championships is up in 2023-24. The NCAA, however, packages men’s basketball separately, selling tournament rights to Turner for more than a billion dollars a year. The ESPN deal, meanwhile, bundles the women’s tournament with the so-called “Olympic sports.” If sold separately, the Kaplan Report estimated the women’s tournament could be worth between $81 million and $112 million per year. And remember, that report is now two years old. Women’s March Madness has grown significantly since then, breaking ratings and attendance records while selling out ad inventory.

It’s going to be worth a lot more than $81 million.

With that new deal, there seems to be confidence that unit distribution will follow.

“I do think it’s coming,” said Megan Kahn, the VP of Women’s Basketball for the Big Ten. “We’re at a point in time where our game deserves this. I think it’s going to put a lot of pressure on the NCAA to look that direction.”

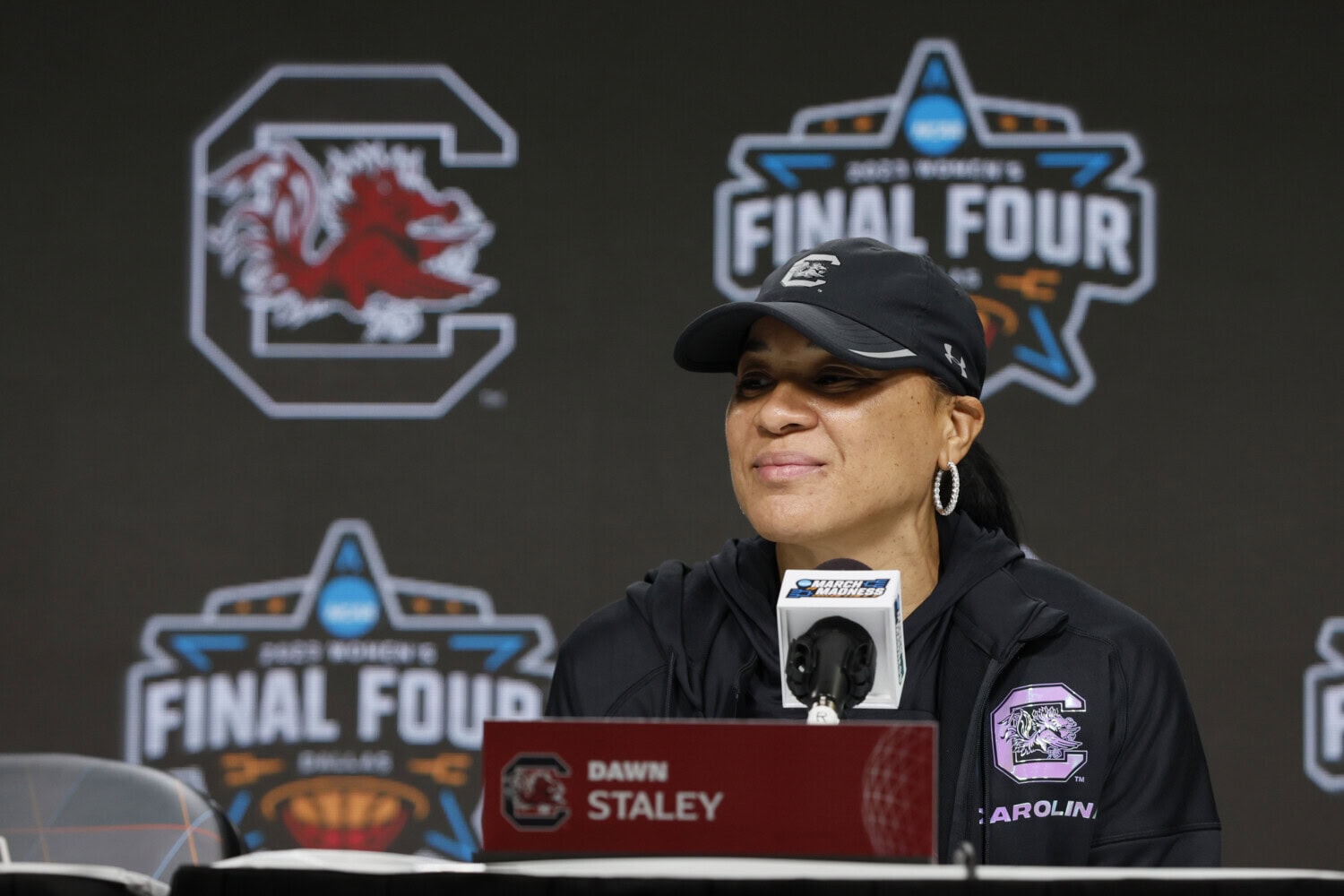

Until that happens, expect to hear the advocates grow even louder. It was a topic of discussion at the 2022 Women’s Final Four, where Dawn Staley (South Carolina), Tara VanDerveer (Stanford), and Jeff Walz (Louisville) all answered questions about it. This year, it was more of the same.

“The units are pretty big,” Staley told the media at her 2023 pre-Final Four press conference in Dallas. “That’s the thing that’s been weighing us down, meaning it costs a lot to bring all of these teams all around the country in the tournament, and if we can bring millions into our athletic departments, I think it would help on our campuses.”

Iowa coach Lisa Bluder agreed, saying revenue distribution units will incentives schools to invest in women’s basketball.

“Athletic directors are going to invest where they get something back from it,” she told the media. I think at Iowa with our fan base, we’ve gotten something back from women’s basketball. But if ADs knew, ‘Hey, if my team makes it to the NCAA Tournament and I get a little money from that,’ it would help some of them invest, if they’re not completely invested in women’s basketball now.”

There is, however, that part that few really want to acknowledge. For now, the women’s tournament is going to bring in less money than the men’s. While ratings are exploding and attendance is steadily increasing, it won’t compare with the billion-dollar monster that is men’s March Madness. At last year’s Final Four, Walz conceded that distribution units for women’s basketball may not be as big as they are for the men’s — at least not yet.

Perko, however, disagrees. She pointed out that the NCAA does not claim to be a business; it’s a non-profit. Because of that, it doesn’t matter where the money for women’s tournament distribution comes from — the NCAA claims in its constitution that it will treat men’s and women’s sports equally. How much the women bring in vs. the men should not matter.

She sees two possible solutions for the NCAA. The first would be to eliminate athletic performance incentives entirely and to find another way to distribute tournament revenue. The other would be to add a women’s component — and she’s open to options as to what that looks like. Maybe it is just men’s and women’s basketball. Maybe there’s a performance component to every NCAA championship. It doesn’t really matter how the NCAA decides to go about this, the fact remains that as it stands now, the organization is defying its own constitution and not treating the two sports equitably.

‘It’s discouraging that two distribution cycles will have passed and $330 million will have been distributed, and the board has been told by its own commissioned law firm that it’s inequitable,” she said. “So the Knight Commission’s position is this is an issue that the, the NCAA Division I board of directors should address with much more urgency.”

When Perko says urgency, she is talking about moving even faster than the Kaplan Report recommends. The report suggests phasing in women’s distributions, beginning at 5% of the overall Basketball Performance Fund and increasing by 5% each year until the revenue is made of a 50/50 split.

“The Kaplan report phased it in because they didn’t want to create a budget crunch for people counting on money,” Perko said. “But the way that formula works is, as a school, you don’t know how many teams your conference is going to get in the men’s basketball tournament, so you can’t count on money that hasn’t been rewarded. So the impact of changing it is not that significant because they shouldn’t be counting on money that hasn’t been given to them anyway.”

Perko says this is actually a great opportunity for new NCAA President Charlie Baker. Baker’s new post is often a thankless one, but he can score an easy PR win by making this a priority. And now, with women’s basketball earning more buzz than ever, thanks to mammoth Final Four ratings and even bigger personalities in the sport, the timing is perfect.

Angel Reese and Caitlin Clark will both return to school next year. So will Elizabeth Kitley, Mackenzie Holmes, and Cameron Brink. Azzi Fudd and Paige Bueckers should enter the season healthy. Next year could, truly, be the most successful season in the history of the sport.

As of now, however, it appears the schools responsible for making that happen won’t see a dime for it. The pressure is on the NCAA to change that.