In tennis, we accept that singles reigns supreme. But is there any good reason why doubles isn’t more of a thing?

ESPN had hoped, and surely planned, on a long day of tennis on Wednesday as the Men’s and Women’s quarterfinals concluded at the US Open.

Perhaps teenager Emma Raducanu takes a set off of Olympic gold medalist Belinda Bencic and takes their match three sets. Maybe South African Lloyd Harris’s dream run into his first Grand Slam quarters would lead him to push World No. 3 Alexander Zverev. If you’d asked those around the game (and consulted the pre-match betting odds), you’d think both matches would be extended.

Then, as has been customary at this tournament, the unexpected happened. Raducanu came back from a break down in the first set and absolutely bulldozed Bencic to a straight-set victory. Harris was broken serving for the first set and fell to Zverev rather easily, three sets to love. Four and a half hours after coverage had begun, play at Arthur Ashe Stadium had concluded for the afternoon.

So, with two hours left to fill, ESPN moved its coverage over to Louis Armstrong Stadium to air a women’s doubles match featuring young Americans Coco Gauff and Caty McNally challenging the top two doubles players in the world, Elise Mertens and Hsieh Su-Wei.

What ensued was incredibly compelling television.

In front of a packed crowd at Louis Armstrong Stadium, the Americans stunned Mertens and Hsieh, finishing off the match with a commanding tiebreaker and bringing the raucous crowd to its feet.

It was in that moment that many Americans were reminded of just how thrilling doubles tennis can be. At the same time, it was a harsh reminder of where the doubles game stands.

It’s very clear the potential that it has, but it’s rarely under the spotlight. It takes a singles star — or a rare pair of doubles specialists with complementary star power — to even see it covered in the mainstream, yet it’s universally beloved whenever it’s on TV or on a tennis court on the grounds of the US Open.

So, why isn’t doubles tennis a thing?

Well, as longtime tennis commentator Brian Clark reminded me, it used to be.

“I think it has taken off in the past, but I think it’s kind of come back down to earth,” he says. “I think star power has something to do with that. John McEnroe is a good example. He was the biggest star in tennis and he would consistently play singles and doubles.”

Of course, McEnroe was one of the biggest stars in the sport’s history and did reach No. 1 in the world in doubles, winning nine Grand Slams in those draws and claiming seven straight titles at the Tour Finals between 1978 and ’84 alongside partner Peter Fleming.

Fans will recall the Bryan brothers years later — identical twins Bob and Mike — who dominated the doubles game for over 20 years until retiring in 2020, holding the record with 139 straight weeks atop the world rankings. Then there were the Williams sisters, of course. Venus and Serena won 14 Grand Slam doubles titles in addition to becoming two of the most successful singles stars in tennis history.

Now, though, without much star power in doubles or a consistent, marketable team to celebrate, we’ve hit a lull in this particular area of tennis. It’s not as if there are recognizable pairings playing all the time; rather, a collection of singles players floats around and mostly chooses new partners every time a Grand Slam rolls around.

“It’s so much more mix and match that it’s hard to really follow,” Clark tells Boardroom. “It’s easy to become a fan of the Bryans. They’re twins. They’re American. They’re really good. When you’ve got a pairing like at [the 2021 US Open], Steve Johnson and Sam Querrey are a good example. They’re singles players, but they’re playing doubles here. It’s harder to follow week in and week out.”

Just this year, Querrey — one of the more recognizable American men on tour these days — played in 10 doubles events and had seven different partners. This is the norm for singles players entering tournaments in doubles, as the schedule of a singles season is simply demanding. Not everyone is entering the same tournaments, so sticking with the same partner for an extended period just isn’t a realistic goal for a player whose priority is ultimately, inevitably singles.

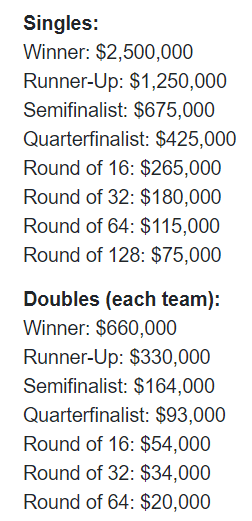

So, why focus on singles at doubles’ expense? Well, for one, the prize money is really good. To put things in perspective at this year’s US Open:

- Both winners of this weekend’s singles finals will make $2,500,000 each

- Singles runners-up pocket $1,250,000

- All men’s and women’s singles semifinalists received $675,000

- Each winning men’s and women’s takes home just $660,000

- The winning mixed doubles team gets $160,000

It’s no small chunk of change, but it’s clear that players would be wise to focus on their singles careers if the goal is to make it bigger than big. And this all becomes more abundantly clear when you consider the fatigue that playing doubles consistently can put on your body — at Grand Slams, it means playing tennis every single day and forgoing critical rest and recovery. At smaller tournaments, it often demands playing two matches per day all week long.

“When it’s week in and week out, it feels like a lot,” says Jill Craybas, a former top 50 American player in in the women’s singles and doubles rankings. “It’s a lot more matches. Even though you’re like covering half the court, it’s still pretty physical.”

That’s why you see more singles players like Querrey, who focus on playing doubles at the Grand Slams and finding some partners during the regular season to get more time on-court. Doubles can hurt your ability to succeed in singles if you put too much into it, but it can also help you greatly improve your singles game as long as you’re not wearing yourself out.

“I feel like it did help my singles a lot as far as returning and seeing new angles of the court, getting comfortable transitioning forward,” Craybas says. “It helped me with learning a lot of different kind of shots, getting better at the lob, getting better at the net…your reflexes get better. When I was at the net, I felt immediately more alert.”

It can also aid singles players who are stuck in a foreign country simply with nothing to do. In March, players from all over the world make the trek to Indian Wells in California for the first Masters 1000 tournament of the year, but with another Masters 1000 just a couple of weeks later in Miami, most players don’t feel it makes sense to travel all the way back home only to return to the United States again.

“They’re gonna stay,” says Craybas. “So a lot of them just want that extra court time…in that case, the prize money isn’t an indicator of whether they play or not.”

So, there can be plenty of non-financial incentives to play doubles, but with the risk of injury or fatigue evident for the best players in the world, they’re not entering in a ton of events around the Grand Slams. That’s where the doubles game is having issues growing.

Without consistency in the pairings and a year full of great doubles matchups at the smaller tournaments like we see on the singles side, it seems like an uphill battle for doubles to become a big part of the sport, which is somewhat sad given it’s the most an average tennis fan can relate to the pros; the vast majority of casual tennis is played in the doubles format.

So, aside from drastically increasing the doubles prize money to match the singles, is there a way to grow that side of tennis?

Clark has an interesting idea.

“Emphasized the mixed doubles,” he says. “You saw at the Olympics the new mixed format sports. There was mixed triathlon and different other competitions like that… if you were to find a way to get more singles players, men and women, to play mixed consistently, that would be the best formula. And then I think to do that you need to figure out how to get it at more events throughout the years.”

It’s intriguing, considering the crossovers through the years have been wildly entertaining.

Nick Kyrgios and Venus Williams were a staple of ESPN’s Wimbledon coverage this year in the mixed doubles draw, where the prize money is so small (roughly $118,000 went to the winner at this year’s Championships). There was also the popular Hopman Cup, which saw the likes of Roger Federer and Belinda Bencic compete side-by-side before it was discontinued in 2019.

Those scenarios could be a way to draw fans to the quicker-paced, thrilling doubles game. Mixed doubles could also be a natural addition to the handful of joint ATP and WTA tournaments held throughout the year.

Doubles tennis is a fascinating business that has seen its fair share of glory days and is currently experiencing a bit of a dormant period. Fortunately, it has Coco Gauff and Caty McNally working for it at the moment, and as long as Gauff continues playing doubles, she should continue to draw national attention to the pair’s matches.

(They’ve got nothing but time, too — Gauff is 17 and McNally is 19. Combining their ages, they’re still four years younger than Federer.)

Perhaps an extended doubles career for Gauff would do the game well, or perhaps adding more mixed events could get more eyeballs on the game.

Until then, the average tennis fan will wait until another match is served up to them by happenstance the midst of their scheduled singles viewing.