Launched by Nike veterans and grounded in resistance, discover how a sports start-up aims to create a new category.

Omorpho means beautiful in Greek, and the definition also applies to an idyllic beginning that start-ups dream of, including the completion of a $5 million seed round with endorsers across the athletic spectrum.

The backstory for the company called Omorpho is even richer.

It was the spring of 2014, and Nike was rolling out the special edition version of its wearable tech takeover, the FuelBand. Made to track and inspire movement, the Apple-compatible accessory was meant to forecast a future of sports where analytics and athletics collide.

Miles away from the brand’s Beaverton campus, Stefan Olander — the motor behind Nike’s digital sport team — was likely wearing a FuelBand while participating in The Murph Challenge. It was an honorary workout tribute for LT. Michael P. Murphy, a veteran who gave his own life in Afghanistan to save that of a fellow U.S. Navy SEAL.

The Murph Challenge, created by Murphy himself, calls for 100 pull-ups, 200 pushups, and 300 squats — sandwiched between mile-long runs — all while wearing a 20-pound vest.

“A buddy of mine brought along a weighted vest to do the Murph Challenge,” Olander recalled to Boardroom. “I was blown away by how it felt different and physiologically how it felt like things were changing.”

The experience of exercising with a weighted vest was both excruciating and invigorating. Though Olander’s Murph Challenge took place so close to his Nike workplace, the aesthetic of the vest felt worlds away from the sleek look of the FuelBand he helped bring to market.

“I was blown away by how ugly it was and uncomfortable,” Olander said. “What if we took this and really put it through a lens or filter that I was used to working with?”

Calling designer Natalie Candrian for coffee, Olander broached the idea of revising the bulky added armor of a weighted vest. Having designed on-court apparel for Maria Sharapova at Nike as well as signature shoes for Tracy McGrady at Adidas, Candrian possessed a unique ability to create products that provided performance solutions for athletes without sacrificing an appealing aesthetic.

The meeting over coffee and the sweat-soaked experience of The Murph Challenge created the foundation for Omorpho Gravity Sportswear. In the years to follow, Olander and Candrian took the major leap of leaving high-profile positions at an industry giant.

Even more cavalier?They challenged the status quo of sportswear while doing it.

Heavy in the Game

Combining almost 40 years of experience in the world of athletic apparel and innovation, Olander and Candrian had long been tasked with adhering to an age-old adage: lighter is better.

Whether basketball shoes or running tops, the competition to cut ounces was paramount among the biggest brands in the space. What few considered to ask was: why?

“Lighter isn’t always better,” Olander said. “We’ve been told that forever, but the only way I’m actually going to get stronger is by resistance. So why hasn’t anyone built that in?”

For years, athletes have added weight to their training regimen to build strength and speed. Michael Jordan famously pushed plates with Tim Grover to outlast the Detroit Pistons. In the aerobics space, ankle and wrist weights were used to tone muscle more efficiently.

Working out is rooted in resistance, but workout apparel is engineered to be the exact opposite. Was it possible for a happy medium to exist?

“When you’re chasing lightweight, you are at some point going to hit diminishing returns,” Olander said. “When that’s touted as innovation, people get fatigued. By flipping this on its head, we’re saying maybe innovation can come through a different lens.”

When working on Omorpho, Olander and co-founder Ben Williams explored the equilibrium idea of MicroLoad. Having already been researched for four years prior, the concept was that the body shouldn’t be overloaded with weight as to impede natural movement, but rather relegated to the right places and the right amounts.

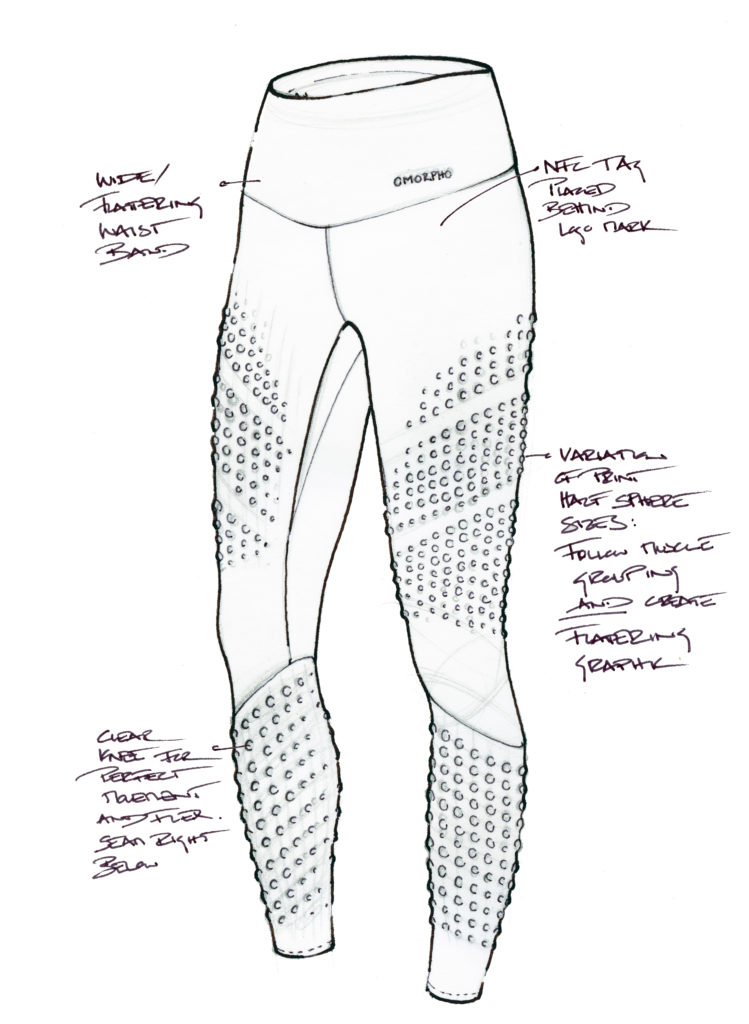

Candrian began drafting designs for vests, tops, and tights tied to this insight.

“It took about 10 ugly ones first,” Candrian told Boardroom. “We literally taped Stefan with gorilla tape to see how it would work. A whole bunch of prototypes later, we got to the final stage about three years later.”

Between three years of prototyping and four years of MicroLoad research conducted in South Africa, the zag became ready for market.

Appetite for Disruption

While Olander’s work on the FuelBand may represent an excitement apex of sport meeting Silicon Valley, the breadth of brand-speak surrounding words like “innovation” and “disruption” has fallen flat where sportswear is concerned.

The idea that every person is an athlete has transcended into the idea that every IP address is a collector. The race is less often to make the athlete faster, but rather to sell the product quicker. Looking good has eclipsed the ethos of playing good.

Ironically inside the corporations that control cool, this wasn’t always the case.

“Fashion was the F word,” Candrian noted on past days of working as a product designer for athletic apparel at big brands.

At Omorpho, she sees an opportunity to create a new performance category untethered to corporate history or mass-market trends.

“You can be with the big brands — and it’s thrilling, don’t get me wrong — but like any job within those big companies, you get hired and set into the tracks,” Candrian said. “You design within the language of the brand.”

While Candrian credits her time at Adidas and Nike as a Master’s Degree in Design, the opportunity to create without walls at Omorpho is riveting.

Olander expresses the same enthusiasm: “We’re actually changing something that hasn’t been tackled. We’re bringing a new way to train, and we are 100% convinced that in a couple of years it will be an entirely new category.”

Olander likens the concept of MicroLoad training apparel to that of when Under Armour introduced its now-famous baselayer tops and tights. At the time, industry powers were uninterested. When it became a half-billion-dollar category, all competitors soon copied.

“They have a lot of fish to fry,” said Olander of the industry’s major players. “The big companies aren’t going to jump on this right away. They’re going to wait and see how this goes.”

So far? It’s going well.

Grounded in Greatness

When Olander andCandrian left the comforts of Nike, a $200 billion company capable of creating with endless resources, the risks were high.

“‘Why would you leave? Isn’t it really hard?’ ” friends asked Olander. “Absolutely, it’s really hard! But that’s the reason for it. If you haven’t done stuff with the safety net before, it’s really thrilling.”

Assembling a team of veterans, Omorpho consists of a crew that’s “been around long enough to know what to look for,” as Olander puts it, and is already catching eyes of athletes.

Because of that, selling All-Pro wide receiver Julio Jones on the product hasn’t been hard.

“When we presented him the product, he said, ‘Send me the stuff, I’ll wear it tomorrow,’” Olander said, smiling. “It’s more people who don’t operate at that level that need convincing. Elite athletes get it in two seconds.”

For elite athletes like Olympian Annie Kunz or BMX star Matthias Dandois, the competitive edge is immediate. Statistics on the Omorpho website display data showing a 9% increase in vertical and 3% increase in speed.

While convincing the amateur athlete to train in weighted apparel is a heavier lift, getting them to love and use the product once they’ve tried it has been light work. Olander shares that the return rate is “incredibly low” with conversions happening on the ground as the brand lacks the budget seen at a Nike or Adidas to traditionally market.

Currently, the brand sells products globally online with a list of North American retail doors to be announced soon.

Inside Omorpho, the appeal isn’t just competing with the Goliath brands the employees once worked at. Rather, it’s creating truly innovative product that pushes athletes to their full potential. Because the body is the equipment in every sport, Candrian and the design team are able to create product in parallel for all genders while appealing to athletes in all sports.

“Free movement is a big part of our insights,” Candrian said. “You still do what you do: your sport, your drills, your warmup. That’s not what you do when you lift weights. As a pro athlete, you can still do the sport that you do, but that increment is pushing you. If you’re Allyson Felix, and you do that when you’re getting out of the gates? You’ll feel like you can fly afterward, which is different than lifting weights in the gym. It’s a new way of training.”

The company is just getting started in 2022. Pro athletes are calling the product their “secret weapon” while the team works tirelessly to improve the category of resistance training apparel that it’s currently creating.

“If it’s rooted in true innovation and true intent, it has longevity,” Candrian promised. “There is no finish line, you’re never done.”